Flying Baked Potatoes

How a little seabird helped save some big trees

(Published in 48-North Magazine last month. It’s a pretty good read, I think, but it’s long enough that I posted the entire thing on the web blog.) I also think I’ve worked out all the bugs on this new software, but if it’s not working for you, please bear with me.

Here’s the story!

“Things are bad – really BAD around here!” he said, “And it’s all because of that stupid owl and the purple murel-thing that shut down the logging.” “You know, that STUPID purple. …bird!” Docks are interesting places, aren’t they? There I was, just heading for our boat and now I was thrust straight into some big environmental debate. Didn’t even know this guy very well, but after I heard his blathering, I took a deep breath and realized I probably needed to stop and do some ‘splainin’ – as Desi used to say. For some reason, I continue to think that a little honest and friendly education might just result in social change at the ballot box, so: “It’s a marbled murrelet,” I answered, “I saw one just the other day out in the bay, fishing with some cormorants. Probably a juvenile from the Olympics or North Cascades. Got a minute? I’ll tell you about them.”

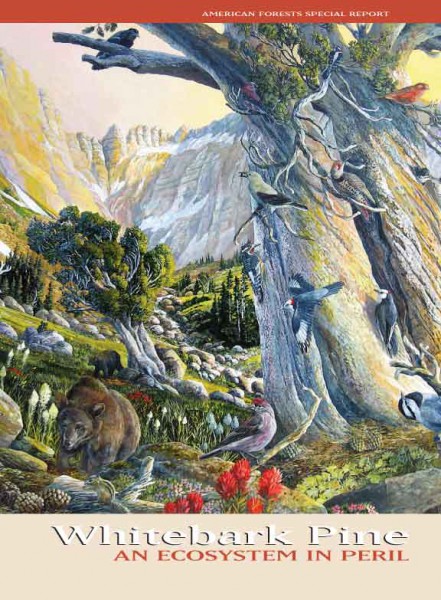

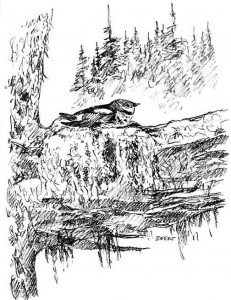

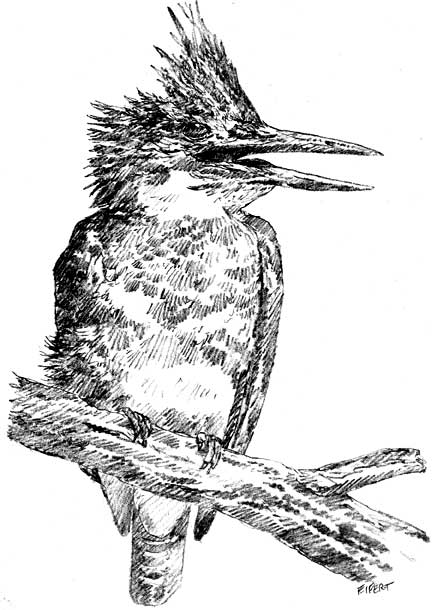

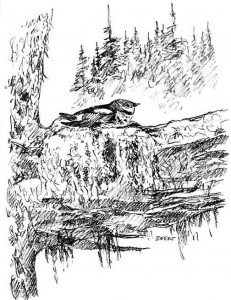

Marbled murrelets! For 30 years I’ve heard them lovingly described by biologists as a flying baked potato with a beak. But not just ANY flying baked potato, for this little chubby ocean bird was once America’s biggest ornithological mystery. While we were putting men on the moon and gloating about how smart we were, no one knew where these local birds even nested. Science ‘discovered’ the murrelet in 1789, but it took another 185 years for us to find a single nest! (Thank goodness murrelets knew where their nests were, or they’d be even worse off than they are.) And while we knew that Alaskan marbled murrelets nested on mossy rocky cliffs, no murreletnest had ever been found between San Francisco and Southwestern British Columbia at the south end of their range. The birds were often seen oddly out of place flying around the big trees in coastal old-growth forests and loggers referred to them as “fog doves,” but why were they there if they live on the ocean?

Then, in 1974, in the Santa Cruz area of California, a tree climber almost stepped on a chick in the canopy of an old-growth redwood, and the mystery was solved. Instead of nesting on mossy rocks, to increase their range southward the birds had adapted their nesting habits to the huge horizontal upper limbs of the giant coastal old-growth, often hundreds of feet in the air, and sometimes upwards of 45 miles from salt water. They hunt for small fish like herring by day in the ocean and return to their nesting duties in the evening. And, what caused this dock guy to think murrelets were Armageddon is that without old-growth trees, murrelets wouldn’t be able to nest on the West Coast of the Lower 48. It’s not just big trees they need, but big horizontal branches thick with moss and lichens, and trees don’t become like this until they’re centuries old. Because of this, and all the logging we’ve done in the past 200 years, the marbled murrelet is now listed as federally threatened and state endangered in Washington (12,000 birds), Oregon (7500) and California (4500). Some scientists believe that it’s not whether murrelets will become extinct, but when, because old forests are now few and far between, and what’s left have badly fragmented murrelet populations. Sometime later this century, when the only birds remaining are small population pockets in our national parks, this strange and unusual sea bird will simply not be viable as a species any more. And if that happens, I hope I’m not here to witness it.

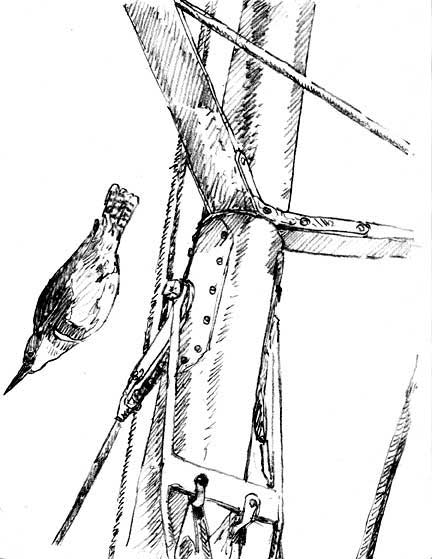

I have some interesting connections with this bird, the one loggers loved to hate and conservationists used as a poster child to halt logging the last few percent of coastal old-growth forests. During the logging turmoil 25 years ago, I spent some time helping research these birds down in California’s coastal redwoods where the world’s tallest trees hug a foggy shoreline. Only 2.5% of the old-growth redwoods remain, and, as an artist I helped draw attention to the murrelets as a way to raise public awareness to the speedy demise of both trees and birds. It was the good, bad and the ugly. Ugly, because, as an artist, I was black-listed by timber organizations. Good, because business was good because of it. And not so bad when I spent one dark and foggy morning at 4:30 am up Redwood National Park’s Lost Man Creek valley, intently listening and watching for murrelets flying from nests to ocean. I remember that listening to murreletcalls in the redwoods reminded me of sailing. Often, when you’re cruising along with little wind to drivethe boat, you can hear that definitive oceanic call of keer, keer, keer. I’ll bet you’ve heard it too. Those are the bird songs of the ocean, not of the forest. I wasn’t a scientist, but an artist just doing his job of observing and responding, but when the National Park purchased one of my murrelet paintings to present to Bush One’s visiting Interior Secretary, I thought I had possibly made a remarkable coup in nature conservation. Now here was art opening the eyes of the powerful. Not so, one park official dryly whispered. This guy was just a patronage placement, a Midwestern pig farmer that didn’t care anything about birds unless they were stewed, fried and on a plate. Where is that painting now – I’d like to know.

Murrelets have a definite ‘look’ to them on the water and so they’re easy to identify. About the size of an American robin, they’re smaller than gulls and cormorants, but here’s the key. They always hold their short bills slightly upward at a different angle than any other seabird, like the graceful angle of a schooner’s bowsprit. Fast fliers with rapid wing beats both in the air and underwater, they spend most of their lives in coastal waters where they court, feed, loaf, molt and preen. These long-lived birds only visit old-growth forests when they do nesting duties, where nests aren’t built but rather squished into place in the moss. Only one egg usually once a year is laid. Incubation lasts about a month with both parents incubating the egg in alternating 24-hour shifts, and chicks fledge in another month. Summer adults have sooty-brown upperparts and are lighter brown below, colors that make them highly camouflaged against the giant trees they’re nesting on. In winter, adults and young become brownish-gray with white wing patches that more closely match ocean colors of wind on waves.

So, let’s say you’re a very young murrelet only a month old. You were born in the top of a two hundred foot tall Douglas-fir up the Dosewallips River in the Olympics. Your parents had chosen THE nest tree just around a sharp river bend near Little Mystery Peak, where they had located a big mossy branch maybe fifteen stories off the ground. The definition of ‘nest’ is pretty casual here; because it’s just a thick bunch of moss your parents had smooshed into a shallow cavity. When you were born, your egg was pale speckled green, the exact same color of the limb’s moss in spring, not like the dried-out brown stuff of late summer or the lush soft green of winter. It wasn’t much of a nest, and so your parents rarely left you unattended so wandering-babes wouldn’t stagger off into thin air. Small fish your parents brought up to eight times a day ended up creating quite a crusty edge to the platform that helped keep you from falling off. And there were other dangers too. Steller’s jays, crows and ravens didn’t often come here before, but thanks to the nearby road that now brings campers and their food, these birds now threaten young murrelets sitting exposed on mossy branches – so you instinctively stayed low. After a month, wings had grown flight feathers and you sensed you were ready to explore. It felt like you could fly like your parents – but how to learn? And where would you go? Then, one evening just after dusk, and with one death-defying jump into space, flight had to be learned in a half second or a much squashed murrelet would have resulted. Somehow it all came together to happen properly, and you were on your way.

It seems a fairly lame way to survive as a species, but you did it anyway – you just walked off that branch and as you went going down at 32 feet per second, you figured it out fast – and in 30 minutes and 20 miles you made your first awkward sea landing in the Hood Canal. I say 30 minutes, because murrelets normally fly at about 50 mph. They havebeen clocked on radar at over 100, so in theory you could make that 20 miles in five minutes, but a first-flight-flier probably wouldn’t do this. In fact, you’d be lucky to do it at all.

As you learned to fly through the giant forest in growing darkness, alone and without your parents as guides, you somehow steered properly towards an ocean you had never seen. In doing this, you were unaided by anything you’d ever witnessed before, and you began a new life you didn’t know existed, began to catch fish untaught by parents you’ll likely never see again, and eventually you’ll nest in a treetop miles from your watery home. Remarkable!

So, when sailing in Puget Sound, the Straits of Juan de Fuca or outer coast all the way down to Santa Cruz, keep your eyes peeled for a small and chubby seabird, head held up like a schooner’s bowsprit and possibly with a small herring in its bill. If its summer, chances are good that it will soon be flying over some of the tallest trees on Earth to hand that little herring over to a chick on a mossy branch hundreds of feet in the air.

Thanks for reading this week.

Larry Eifert

Click here to go to our main website – packed with jigsaw puzzles, prints, interpretive portfolios and lots of other stuff.

Click here to check out what Nancy’s currently up to.