| By Larry Eifert

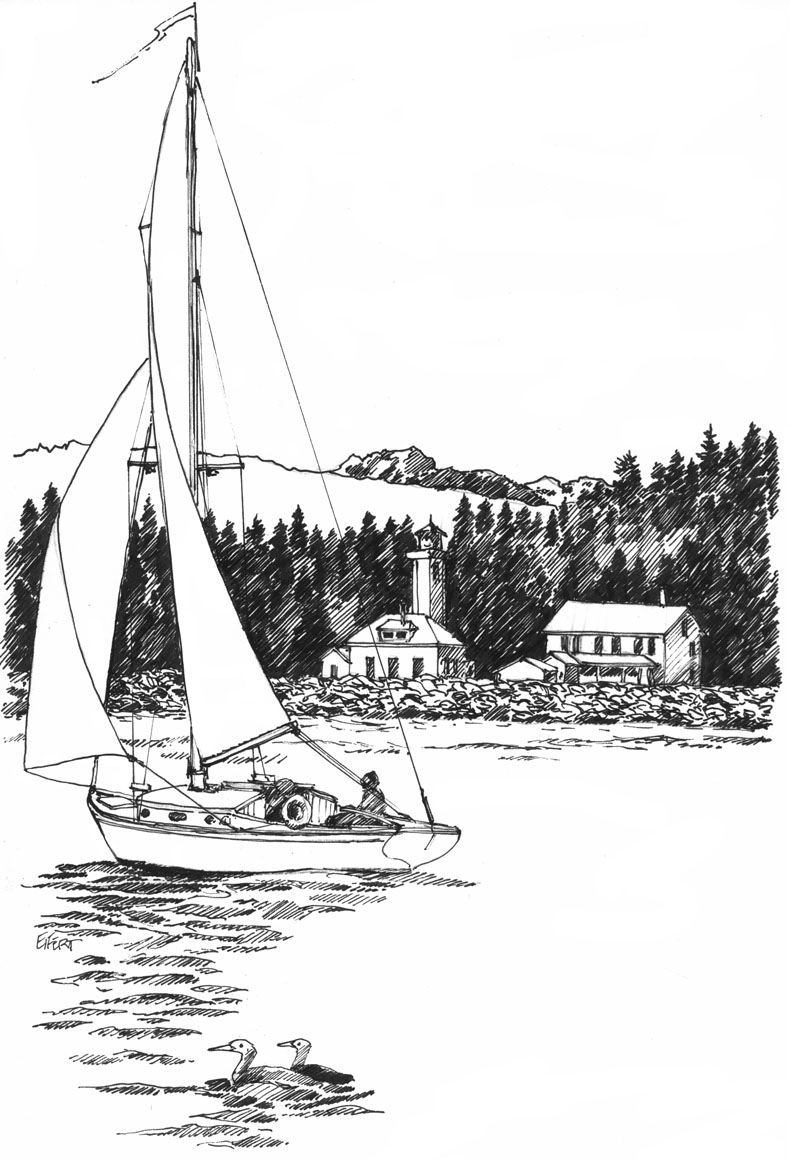

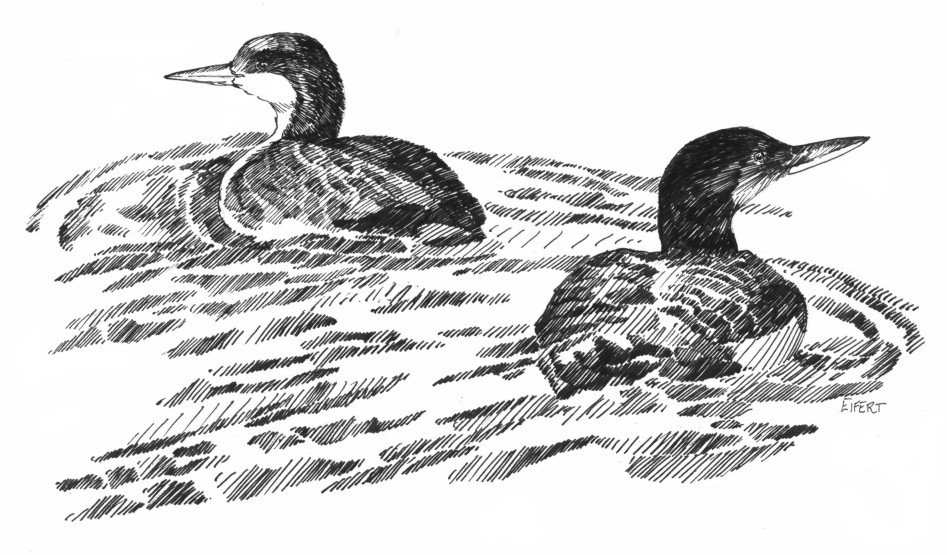

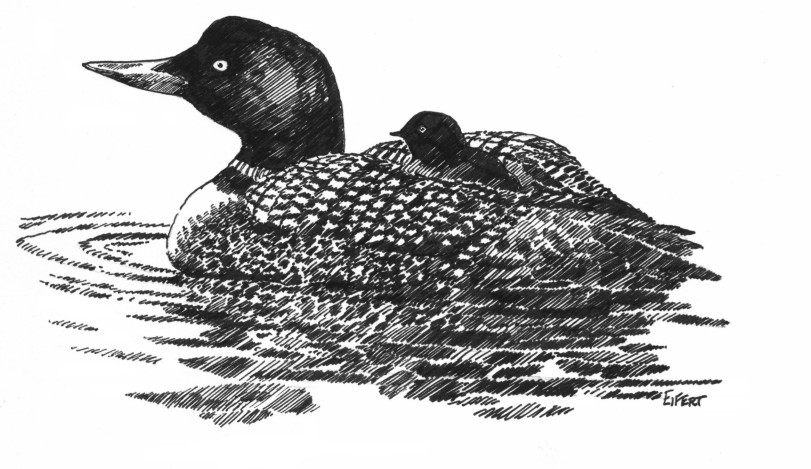

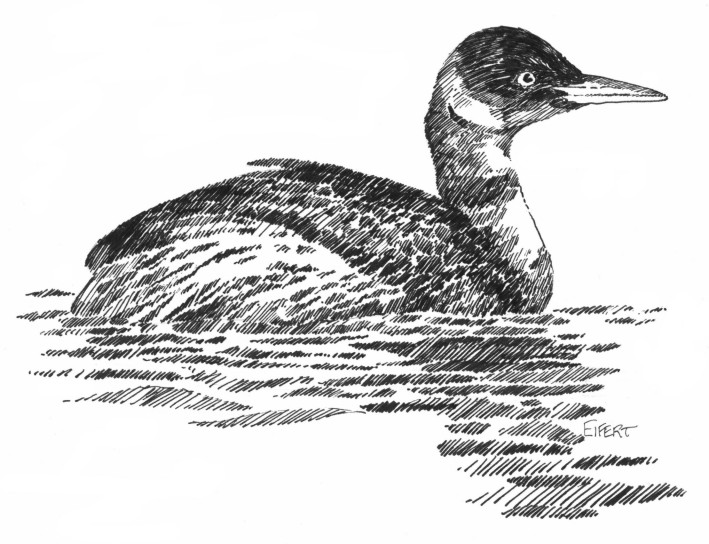

Originally published in the Seattle Times newspaper, December 26, 2005 This could be a misplaced article from the Tucson Times or maybe the Baja Insider, a story about those northerly folks looking to escape chilly winters for a bit of southerly warmth. The idea is correct – the location isn’t! Sea Witch off Point Wilson, entrance to Puget Sound. Sea Witch left the dock with a load of folks on a chilly but sunny winter afternoon. If it is 45 degrees F, sailing into a 10 knot breeze makes it feel like it’s really 32, and, so far today, it hadn’t reached 45. We were on a mission, a find what some call Snow Birds, those elusive northerners that spend their winters not in Arizona, but right here in the Northwest. While we hope to do the same thing, spend a few weeks in a southerly climate drying out and warming up, there are thousands of real birds that do the same thing, they spend their winters here in Puget Sound. As we passed Port Townsend’s picturesque downtown and headed northeast, we knew exactly where to go. As planned, it was the end of an outgoing tide, and ahead on the left the bell buoy at Point Hudson was clanging away, the typical crowd of seals fighting for space aboard Number 2. Here, we turned slightly west and rode the tide towards the point ahead, Point Wilson, where the Strait of Juan de Fuca meets the waters of Puget Sound. In the Strait of Juan De Fuca, a 7.2 foot tide at Cape Flattery will reach Port Townsend 3 hours and forty minutes later and increase in height to 7.9 feet. The tide will reach the south Puget Sound area one hour later and increase to 13.5 feet. Extreme high tides of 18 feet have been recorded in Olympia. Simply put, that’s a lot of water moving about. Four times each day, on each flood and ebb, millions of gallons of water push past Point Wilson lighthouse, the juggernaut of Puget Sound, creating an upwelling, mixing and funneling of nutrients that bring fish and other creatures to an aquatic smorgasbord. And here we had come to watch the diners. (We actually didn’t need the boat; the lighthouse is close enough to the action that binoculars or spotting scopes could provide close viewing too, but then why have the boat?) Pacific Loons We weren’t disappointed. In the first tide rip, a pair of Pacific loons looked sleek in their satin gray winter plumage. Once thought of as the same species as the Old-World’s Arctic Loon and smaller relatives to the common loon, this pair were diving together and coming up with fish each time. Ahead we could see many more. These birds nest on tundra lakes far to the north (I mean REALLY far to the north) near the Arctic Ocean, yet Puget Sound and the Strait of Georgia have one of the highest winter concentrations in the West. In some places, you might see a hundred of these birds in a square mile. In the Strait of Georgia, rafts of up to 1000 have been seen. Common Loon and baby Anything but common, common loons were here too, and difficult to miss. These are big heavy birds, streamlined for swimming underwater after fish, yet almost unable (like most loon species) to walk on land. A beloved bird of the far north, these loons have almost legendary status among naturalists and Native Americans. Whoo,oo,oo, who doesn’t recognize the call of the loon, that ethereal chilling cry that epitomizes the very word “wilderness.” I wish I could better describe the haunting beauty of that red eye and silver spotted necklace better, but I’d get mushy about it. Red-necked Grebe There were suddenly other birds here too, some of the highly migratory grebe tribe. Grebes – well, think little submarines. Like loons, grebes have solid bones, allowing them to literally sink straight down beneath the water’s surface. With some, like the pied-billed grebe, a head might suddenly appear, periscope around to check things out, and then sink to vanish again with almost no action at all. Western grebes, their long graceful necks supporting a head sporting a yellow bill and red eyes, nests in the Canadian prairies, yet winters on the coast from Alaska to Baja. In spring, rafts of a hundred birds just hang out in our backwater bays. In Port Ludlow one spring we witnessed the western grebes amazing ‘spring dance,’ when several pairs launched into a ballet involving a long light-footed sprint across the water’s surface. Red-headed grebes, a similar species with a more compact body, white cheek patch and dark eyes were here in the tide rip too. These birds nest in Canada and Alaska too, and winter on both east and west coasts. And, like most grebes and loons, as their offspring mature they ride on their parents backs using feathers as soft car seats. Bird watching! So what’s the big deal? Let’s see if I can explain it. To watch, really watch these birds is to witness something we’ve lost in our daily urban lives. It’s bringing the scent of wilderness right too us. That these birds have flown thousands of miles, have the ability gained from thousands of years of refinement to find their way from their distant homes to our backyard is to witness something fresh. Watch their eyes, the centers of their avian souls, the eyes of wilderness, as they go about their search for food or social exchange. Notice the shy look of that female as she appears to not be interested in a possible mate for next season. Check out the male in the beginnings of a possible love affair that will try his abilities to the limit. Look and learn, and you’ll probably see something very akin to your own blunderings in that arena. Get a bird book. Grab a pair of binoculars, then, on a boat or afoot, spend some time this winter checking out the snow birds. ***previous*** — ***next*** |