Larry Eifert – First published by the Seattle Times, July 28,2005

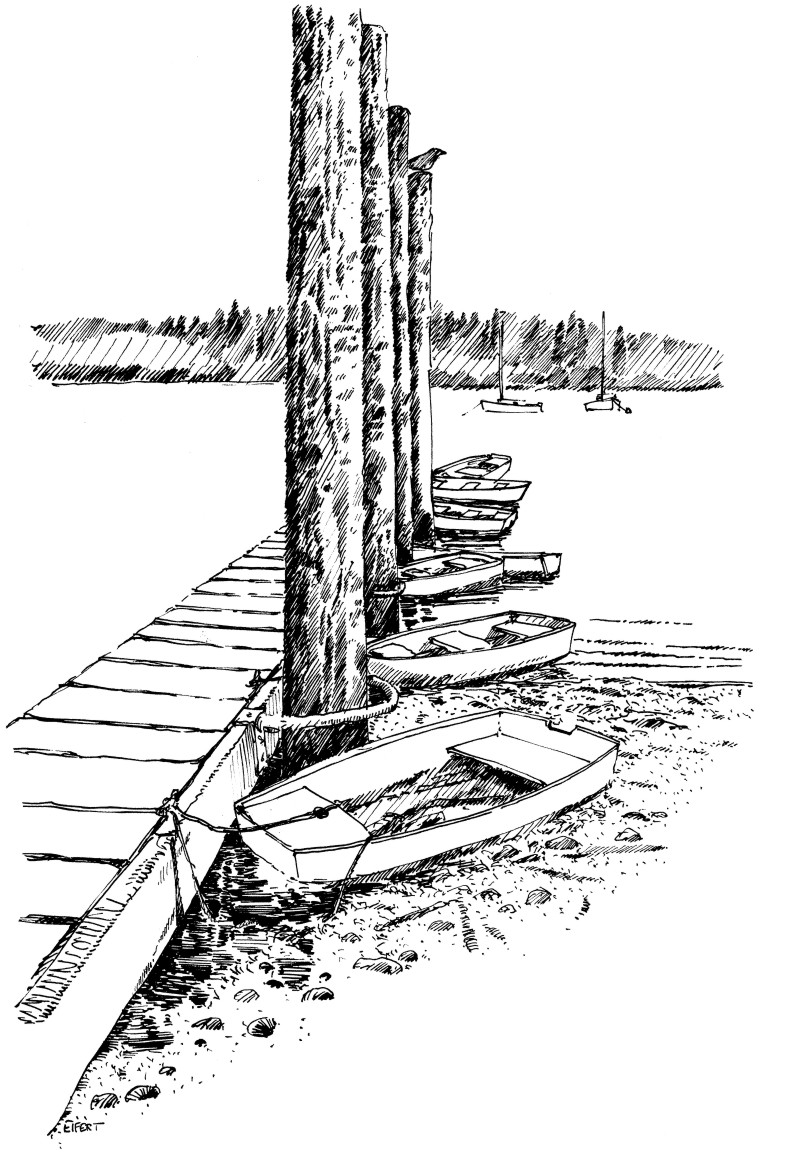

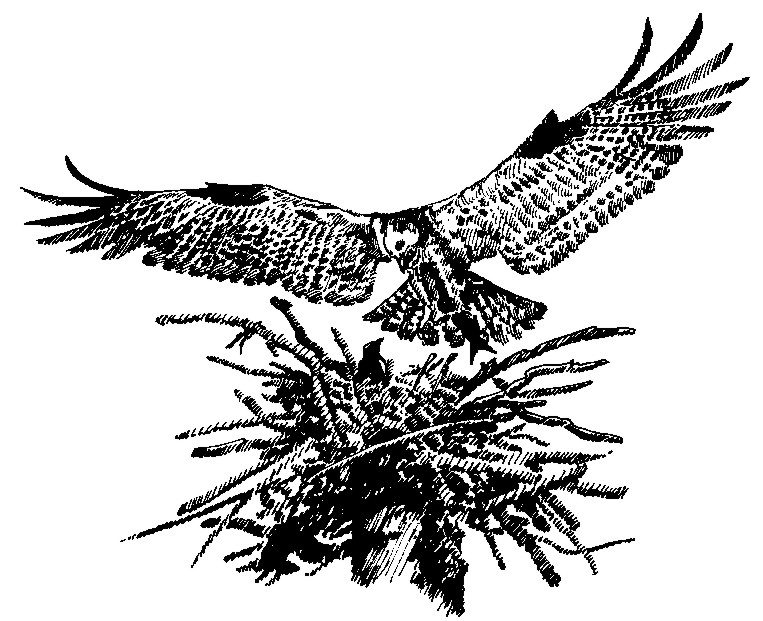

The dingy dock in Mats Mats BayFloating on the wind, the osprey seemed not to even notice as our boat approached! Then, suddenly, the big bird stopped hovering, plunging directly into the channel ahead of us – and immediately launched itself back into the air clutching a fish. Skewing the wildly-flapping salmon around with its feet so it was better balanced and aerodynamically correct, the “fisherman” flew up the narrow channel, disappearing into the deep forest ahead. Dinner was served. The dingy dock in Mats Mats BayFloating on the wind, the osprey seemed not to even notice as our boat approached! Then, suddenly, the big bird stopped hovering, plunging directly into the channel ahead of us – and immediately launched itself back into the air clutching a fish. Skewing the wildly-flapping salmon around with its feet so it was better balanced and aerodynamically correct, the “fisherman” flew up the narrow channel, disappearing into the deep forest ahead. Dinner was served.

The osprey lands with dinner

For centuries, mariners have kept log books or running journals of their ship’s events. In old navy ships, such as the one portrayed in the recent movie, Master and Commander, the log was a place where a ship’s position, wind and wave conditions, sail changes, notices of men flogged for shipboard drunkenness – the normal daily stuff – was all chronicled. Today, most sailors still keep logs, and, being an artist, a painter of wildlife and nature, my skills lean towards keeping a rather colorful version. If a painter is going to jot down the comings and goings of one’s boat, journal entries tend to go a bit beyond that old salty stuff about wind and tide and on our boat flogging doesn’t occur all that much anyway.

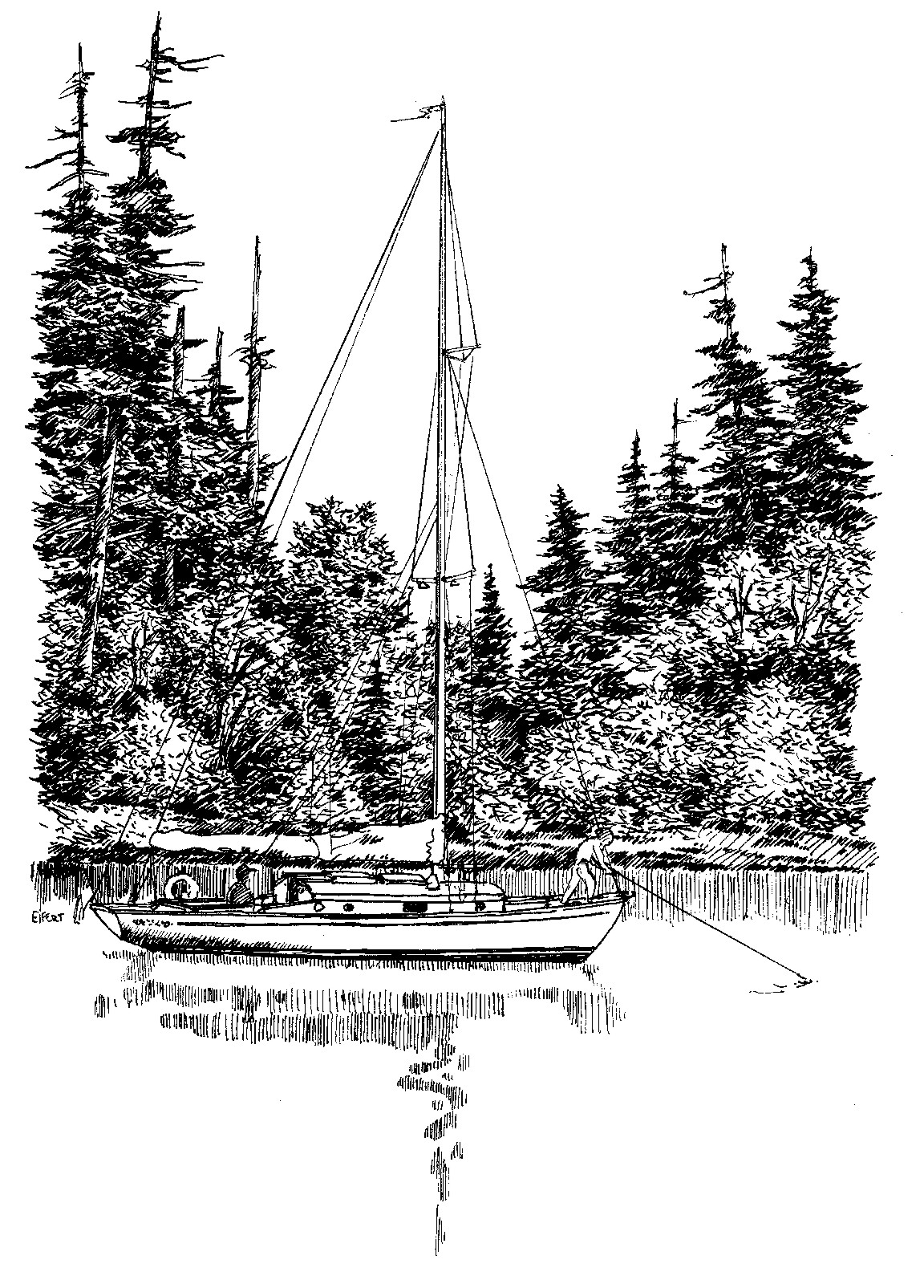

The crew aboard Sea Witch drops the hook

Sea Witch, our little 1939 wooden sloop, was aimed towards Mats Mats Bay, that secluded little pocket harbor just north of Port Ludlow on the Olympic Peninsula. This little hidden bay’s name seems like it needed to be said twice to be noticed. Certainly, coming in by water, if you didn’t know it was there you’d never find it. Entering it the first time requires some divine intervention and hopefully not from Thalia, that minor Greek god of comedy. The entrance is guarded by an underwater rock pile, seemingly mismarked by two buoys that appear to indicate a channel. Instead, the rocks are between the markers (a comedic tragedy just waiting to debut) and these rocks are famous for ripping boats apart before they even begin down the channel into Mats Mats Bay. Steering into that little entrance channel also requires some concentration to line up two range markers, but beautiful Douglas-fir and red cedar overhang the shoreline to just a few feet of your boat and a belted kingfisher’s yack, yack, yack usually fills the air. There’s just too much good stuff here to look at. Then, a sharp dogleg turn to port and the little bay opens up into a secluded and downright romantic little anchorage. There are a few boats anchored in there and some appear not to have moved in years. A few houses that dot the shoreline, but it’s still a quiet peaceful place to spend the night.

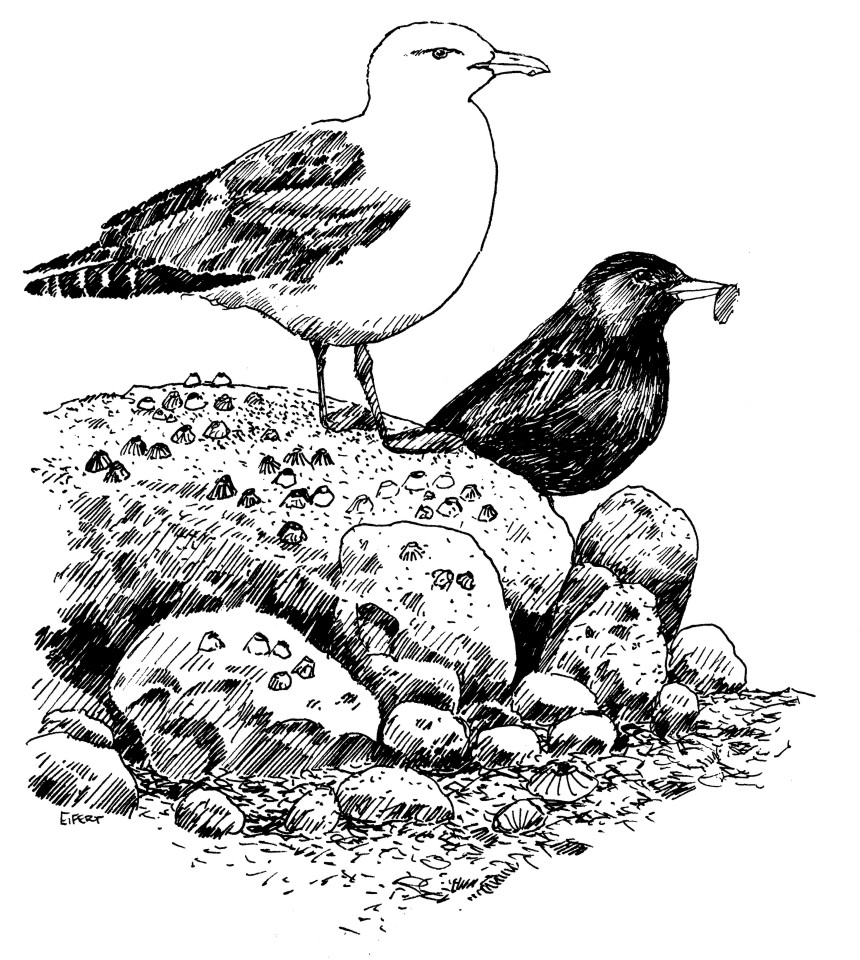

As we entered the little cove, Nancy was standing on the foredeck with chart in hand, attempting to locate the most perfect spot to drop the hook and the skipper/artist”s mind was already making other observations. While our ship’s log might later read: “Anchored in 2 fathoms at low tide, fair holding in mud and sand. Barometer rising to a promising evening,” it will also state: “glaucous-winged and western gulls on the beach hounding Northwestern crows for shellfish. Two pigeon guillemot pairs, those black diving birds with crazy red bills and red feet, were fishing at the far southern end of the bay. Wonder where their nests are”?

Rugged cliffs of Olympic Peninsula basalt rose over the shoreline by the nearby quarry, so that would be added as well, along with a comment or two about the early evening bird songs coming from the seclusion of the nearby forest. Sound travels well across calm water and at only hundred yards from shore, the clear flutelike echos of a Swainson’s thrush rolled out and spread over us like a symphony. To the left and atop the tallest Douglas-fir was a big nest and we could see an osprey up there, its young being fed morsels of that fish so recently in the water beneath us. Ospreys are very successful at catching fish because they are the only hawks that have toes that rotate backwards to better hold their catch. Bald eagles can’t do this and often harass and rob ospreys of their fish by dive-bombing them. All this, of course, was more “food” for the log book.

Crows and gulls on the beach

A kingfisher with dinner

To me, keeping a journal means adding sketches along with the words. A boat at anchor silhouetted against dark conifers, the old fish farm docks gone to rot and an even older purse seiner tied there waiting for a fishing “opening” are all subjects waiting for the pencil of someone making a journal, boat journal or otherwise. These days it may be easier to snap the scene with that digital camera you got for Christmas, but the satisfaction of creating your own pictures, your own history, with your own hand is unmatched. Yes, it takes more time to sketch and write than using a camera, but isn”t spending time out here what you came for in the first place? The very act of field sketching teaches us to “see” better, sharpens our eyes. With a camera, you just point and click. Did you actually SEE that scene? Journal sketching means not just looking, but observing real details, the curve of a shoreline, the bend in that tree, the way black rocks reflect in green water, and by doing so creating a lasting memory of that evening in Mats Mats Bay aboard Sea Witch.

***previous*** — ***next***

|