When it’s time to paint something else!

I sail around in my little boat (whichever one I have currently – there have been 6 – 6 break-out-another-thousand stands for ‘boat’). It’s a floating studio, and learn about what I’m seeing. I’ve done this for decades, but since 2012, I’ve made one-page art stories of these little journeys for 48 North magazine in Seattle, 118 stories total, once a month without fail.

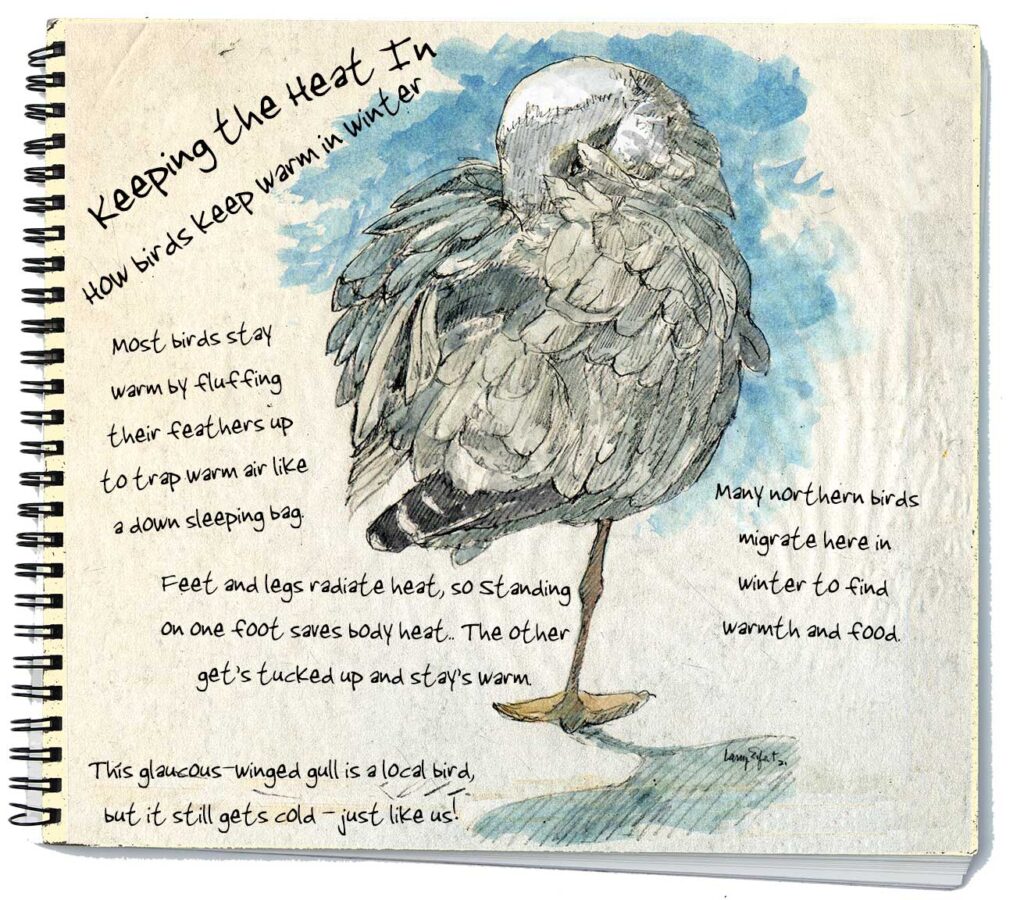

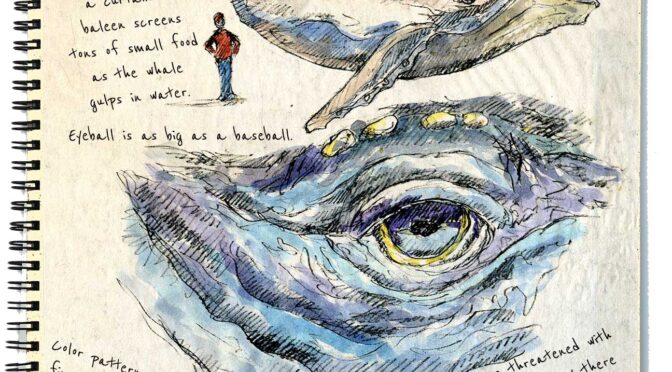

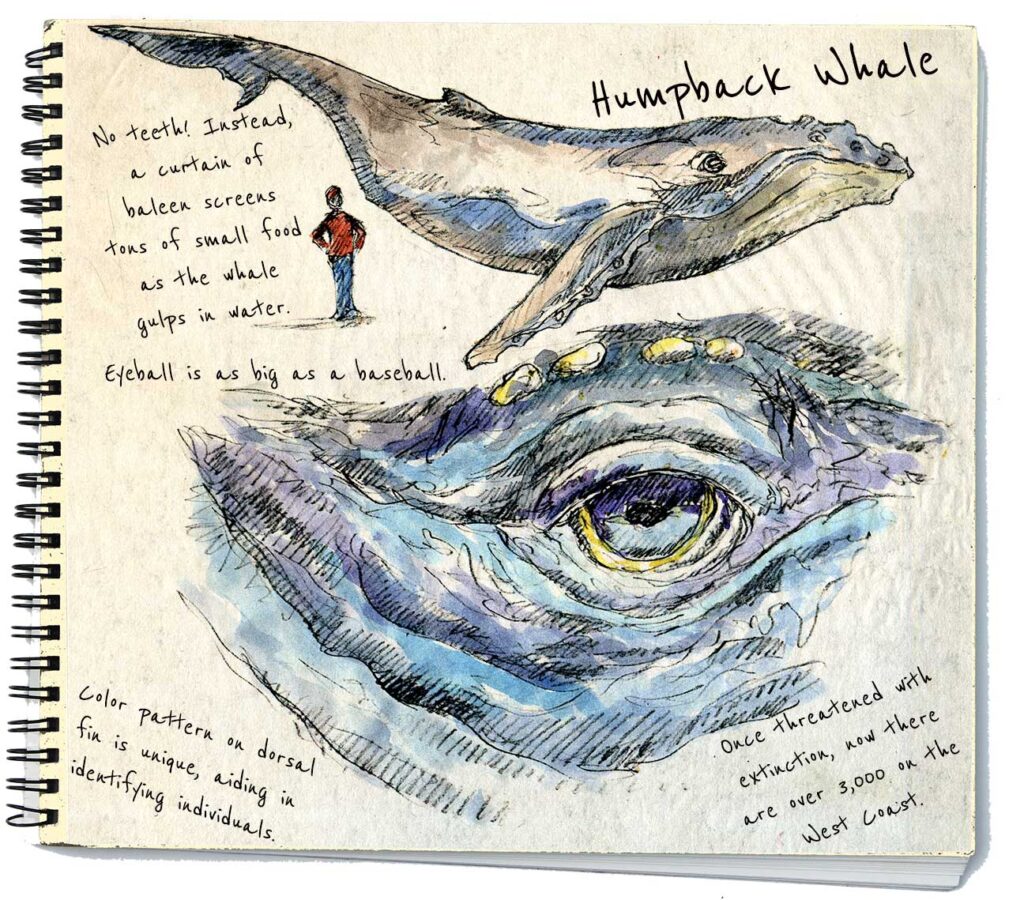

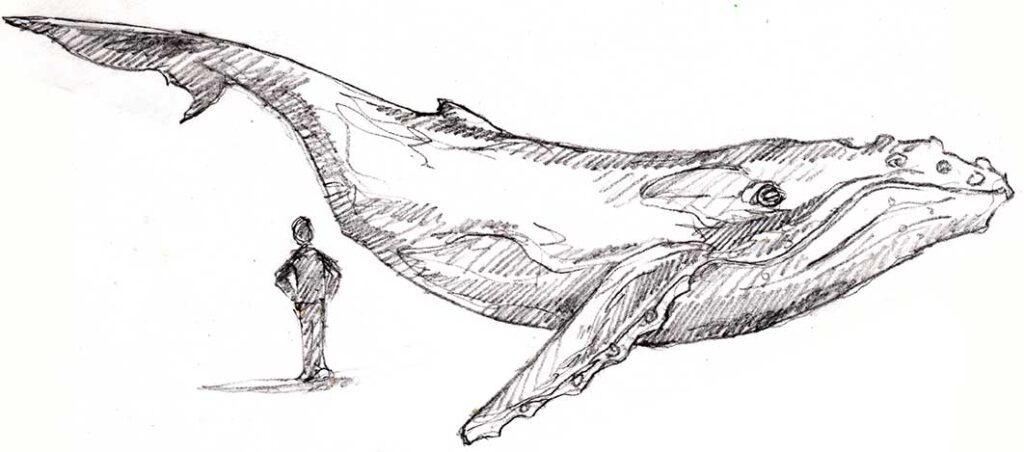

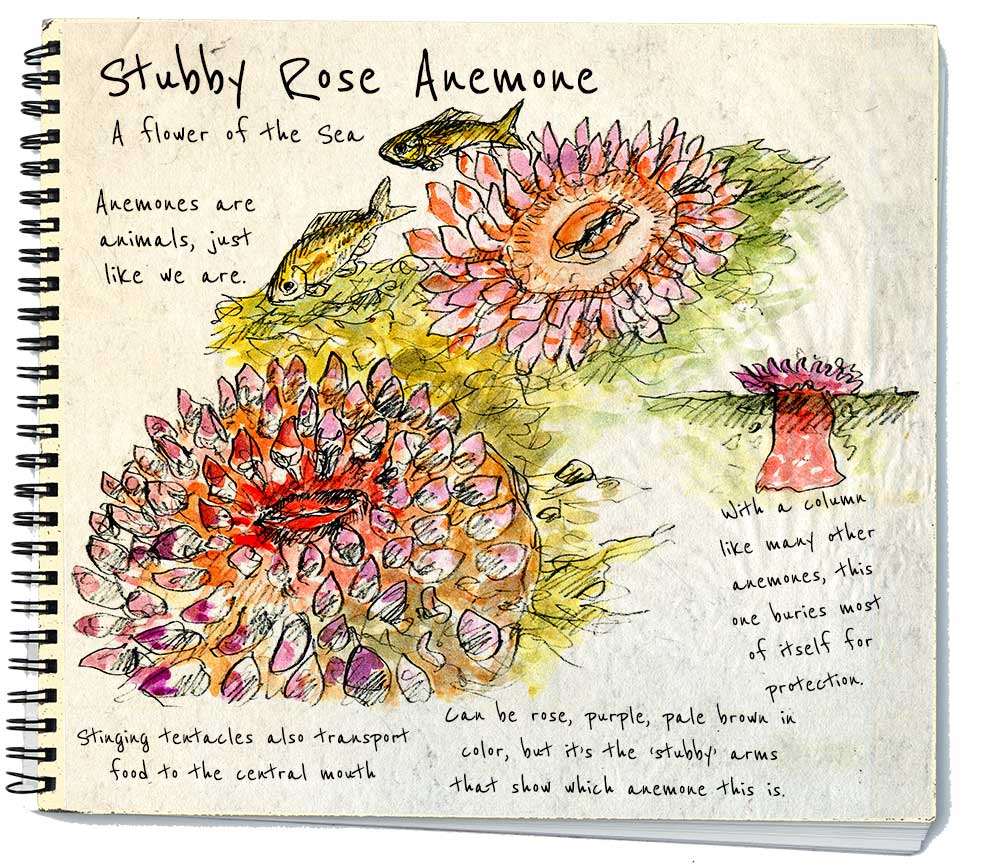

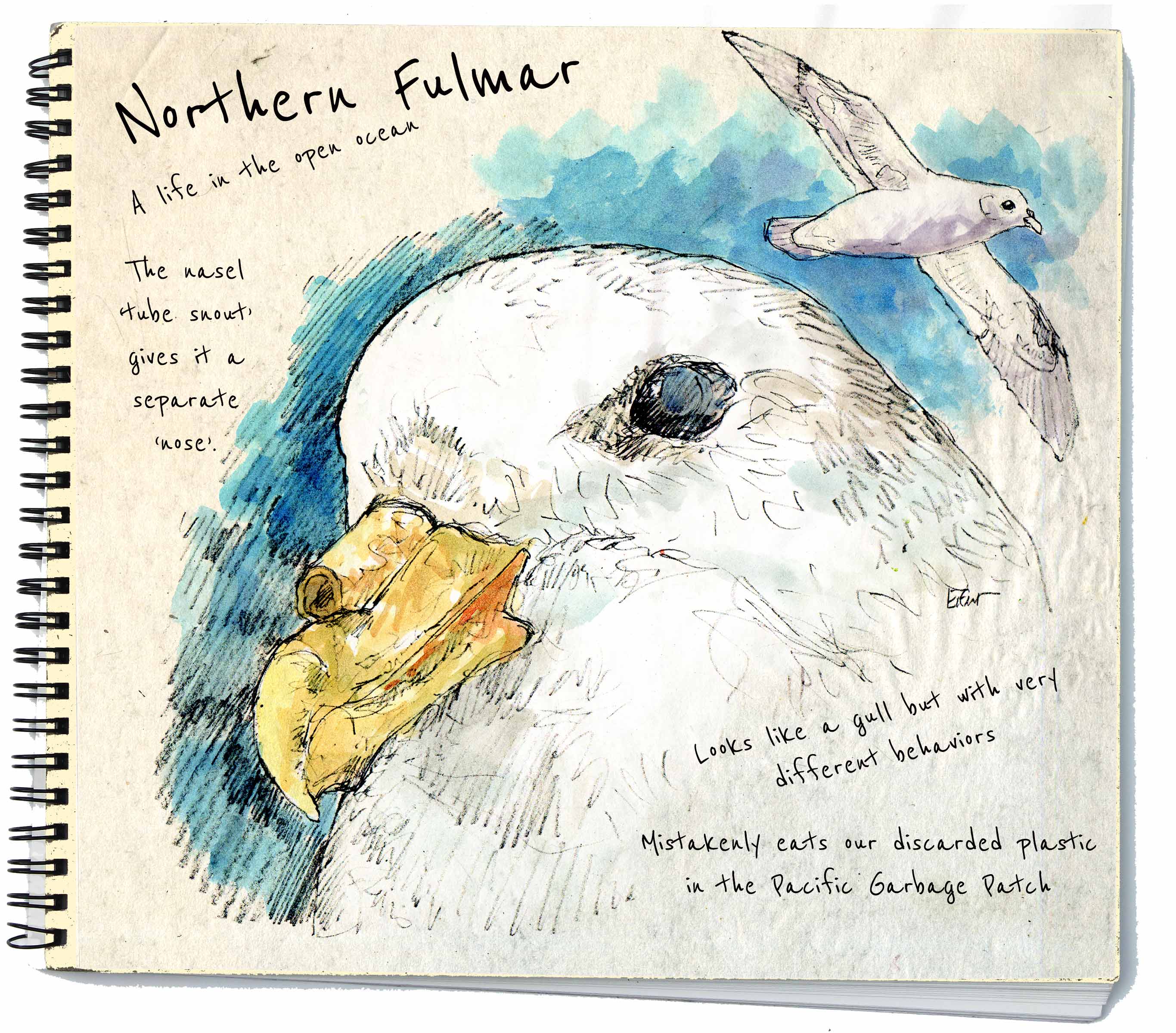

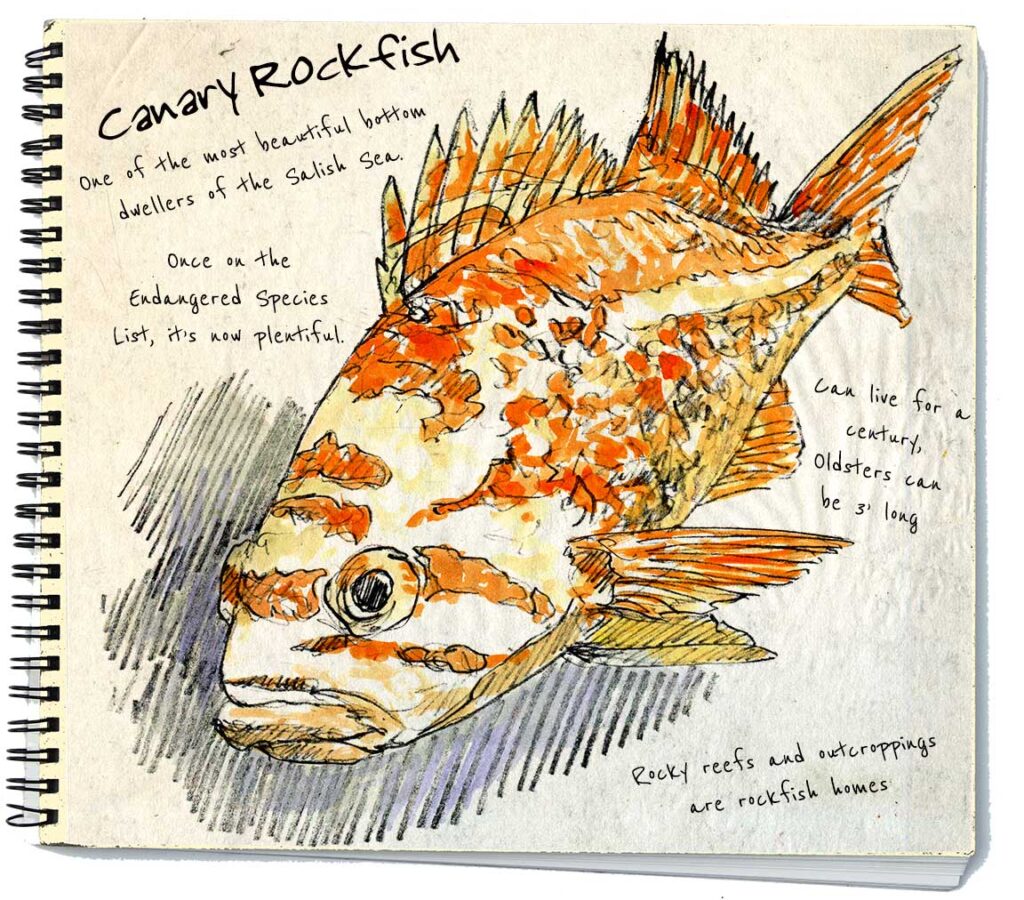

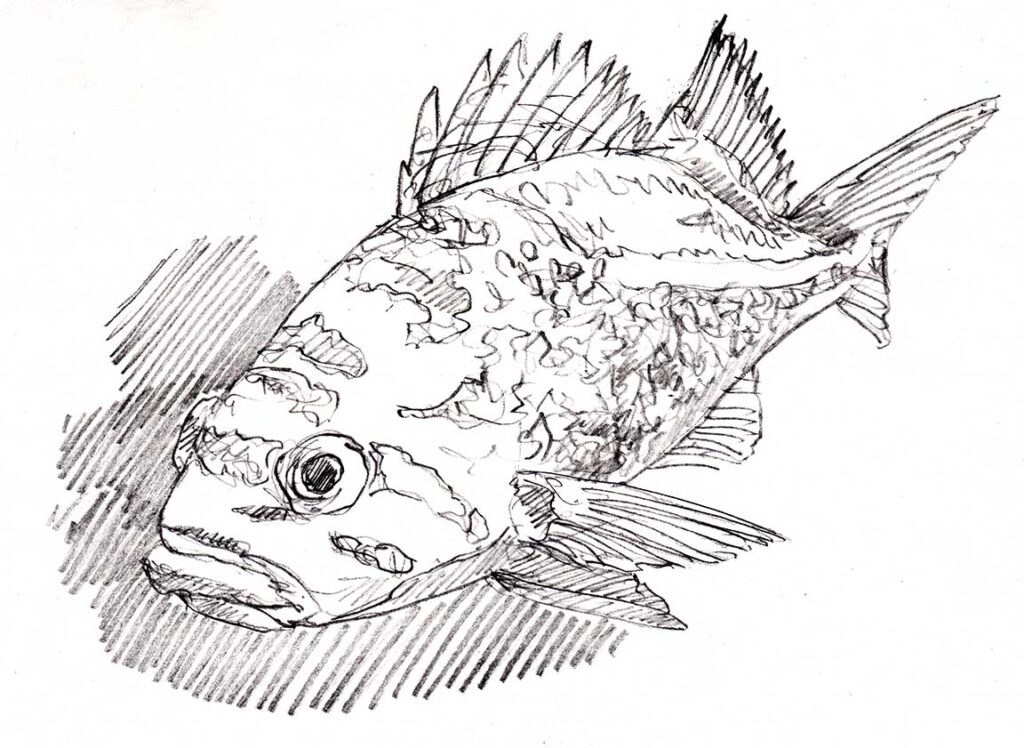

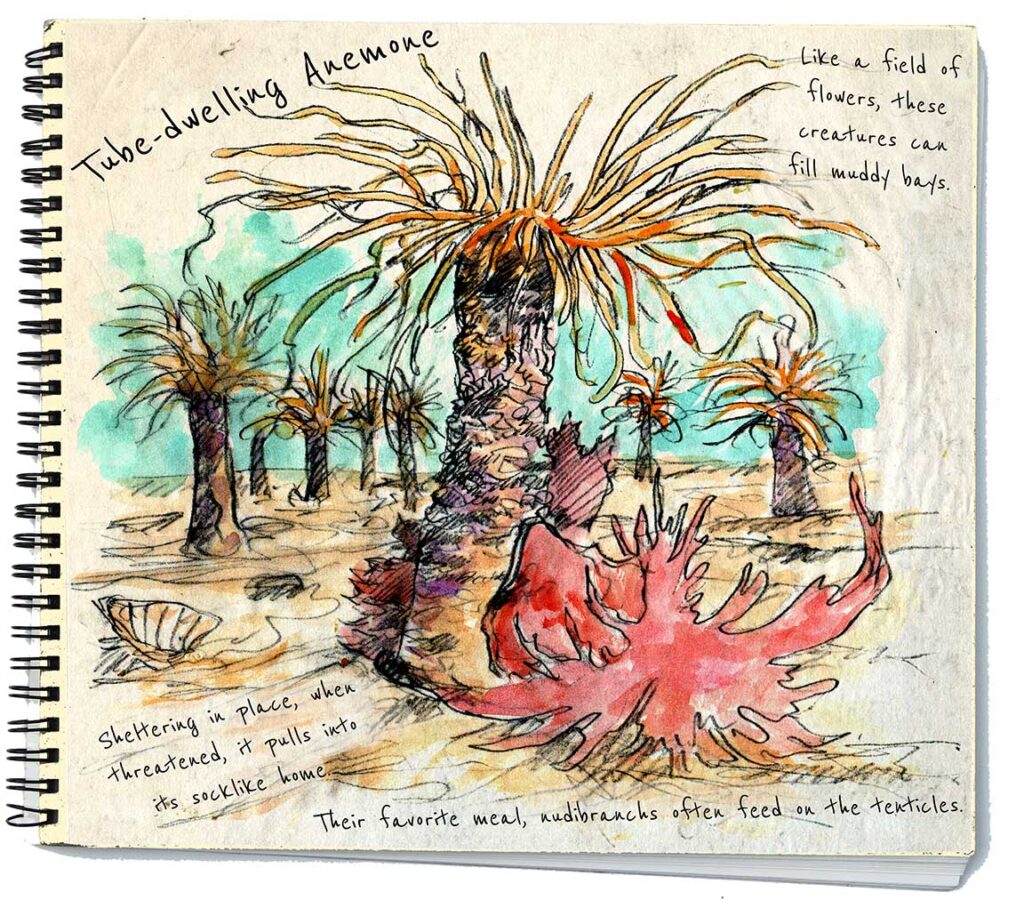

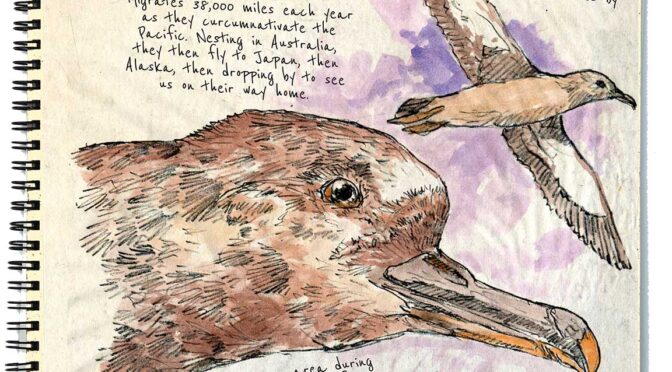

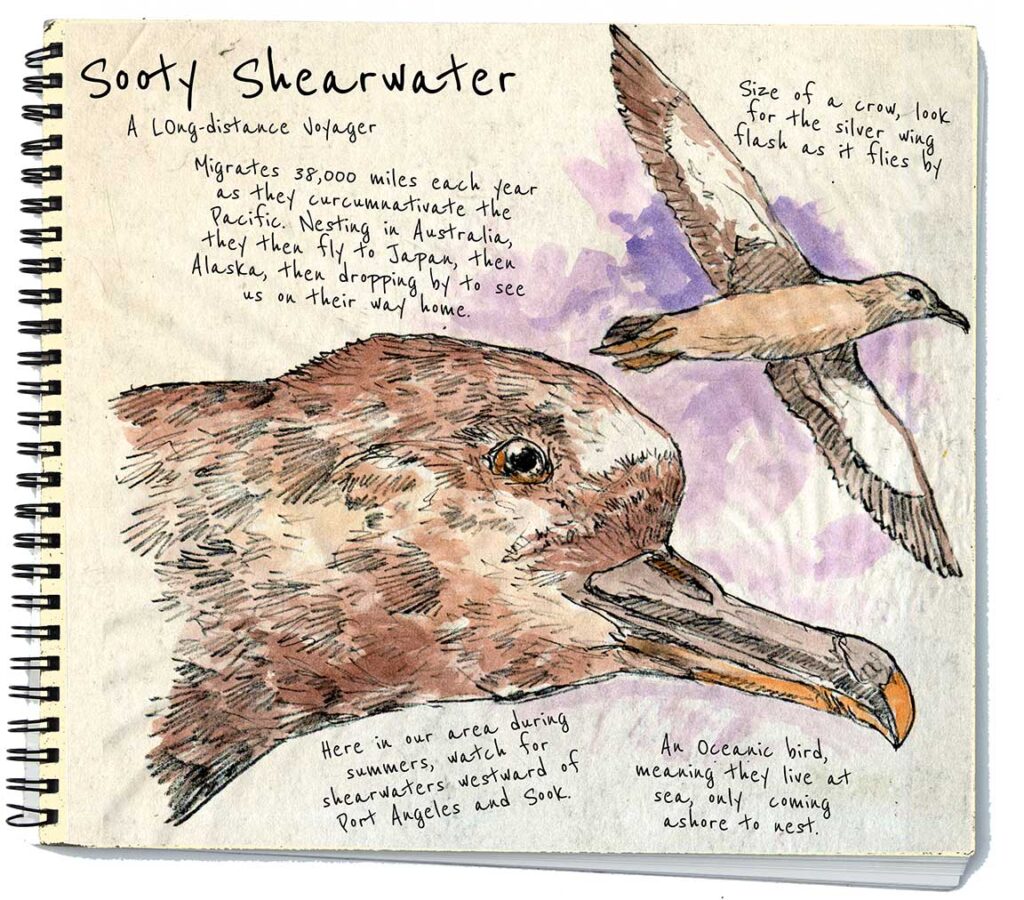

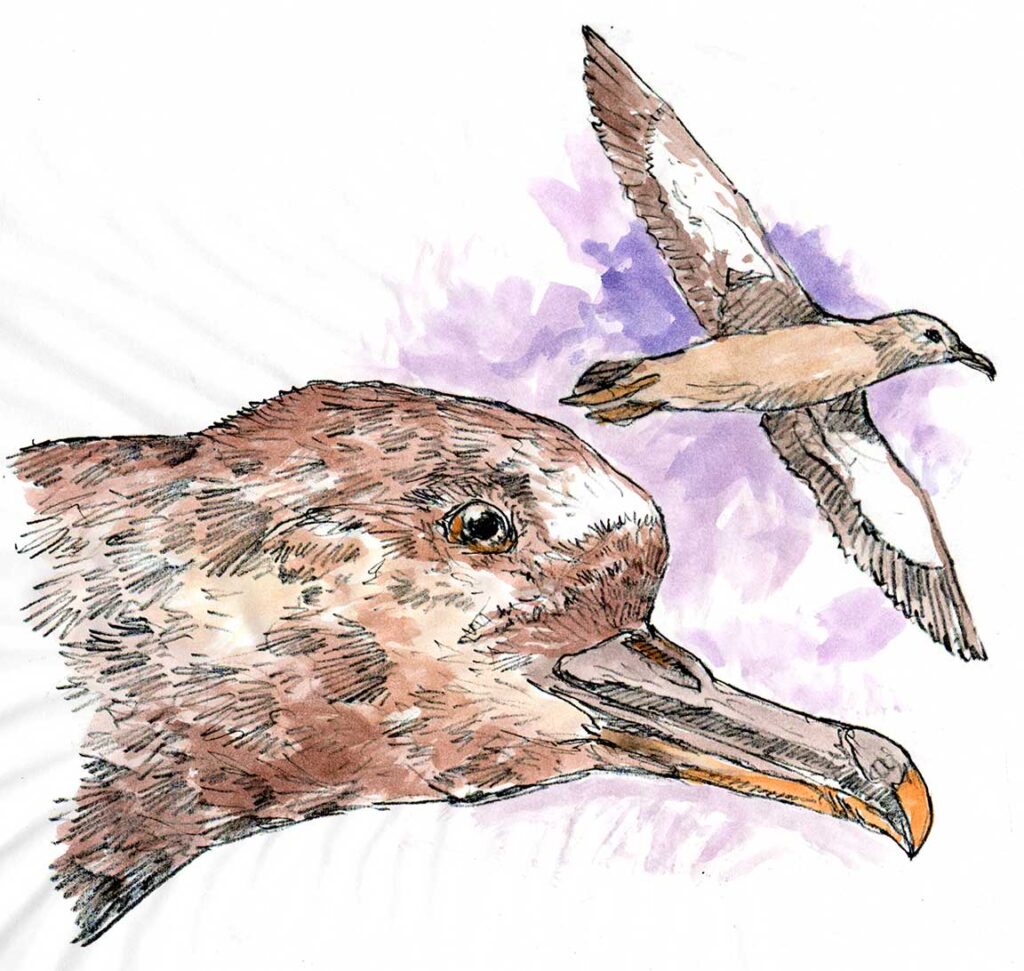

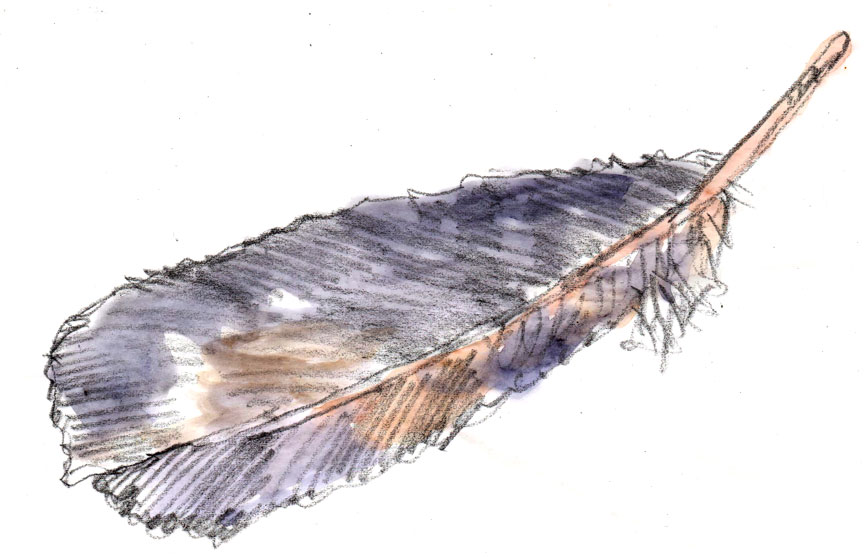

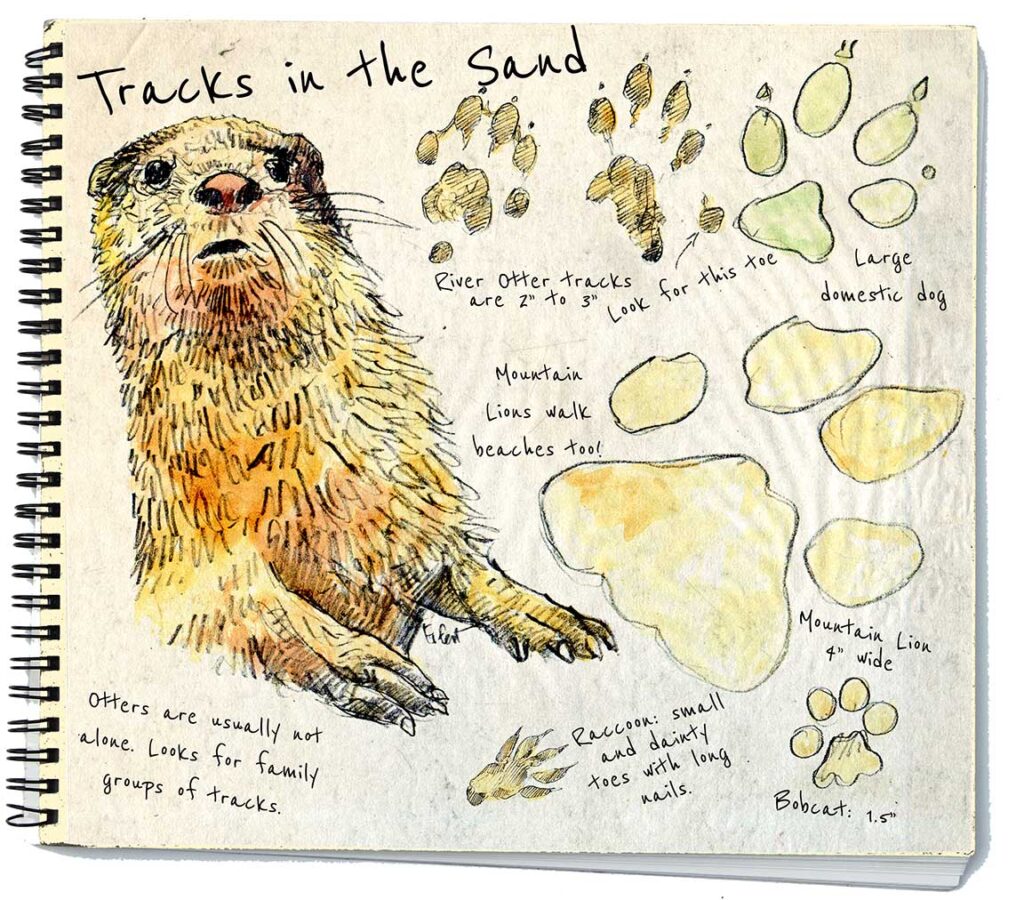

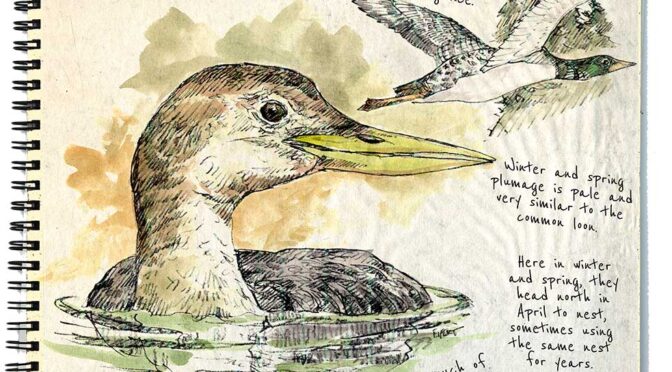

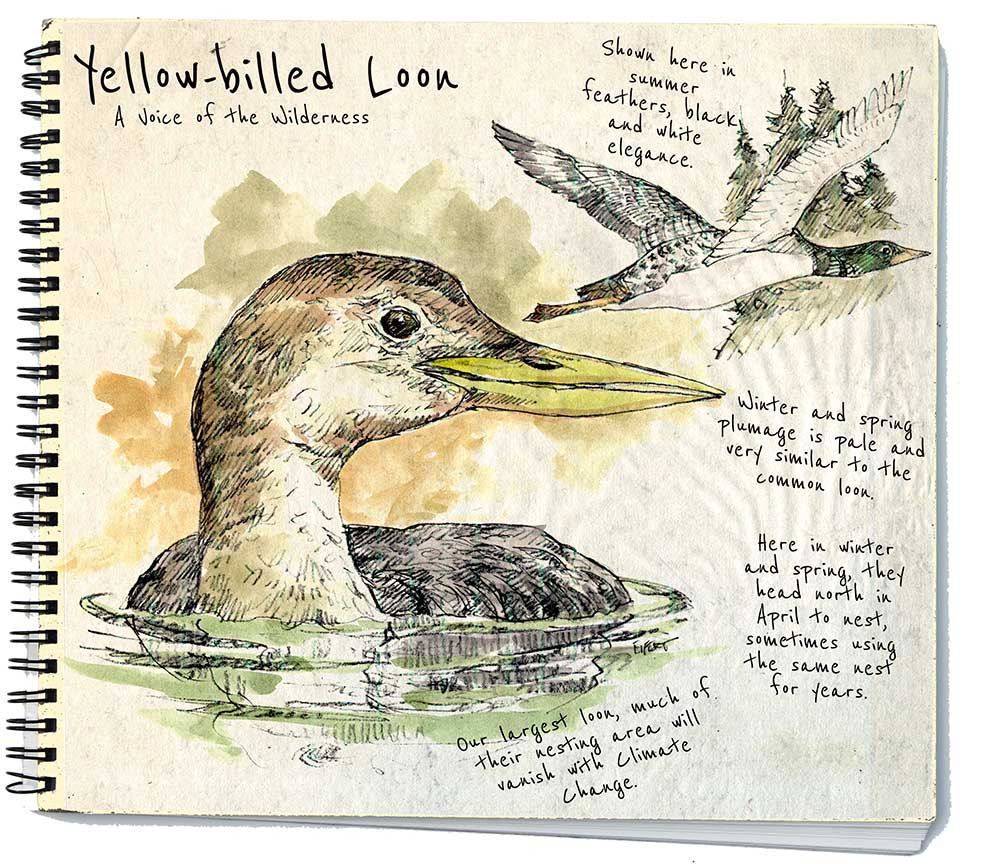

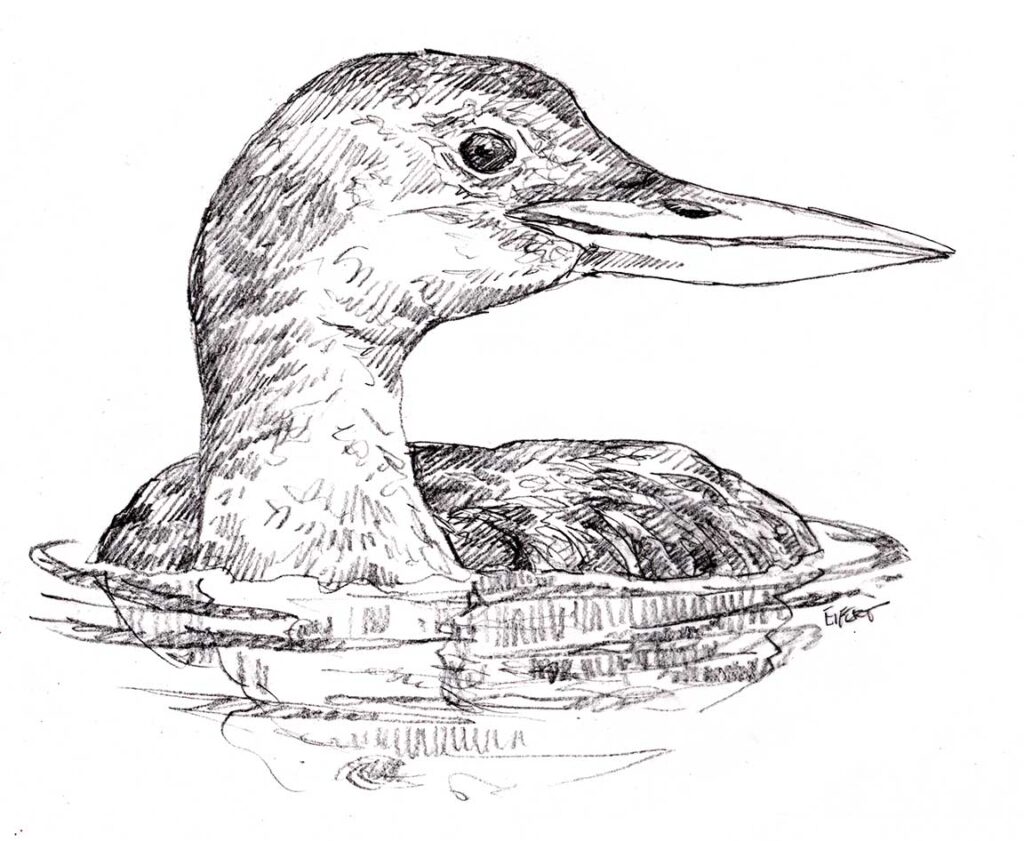

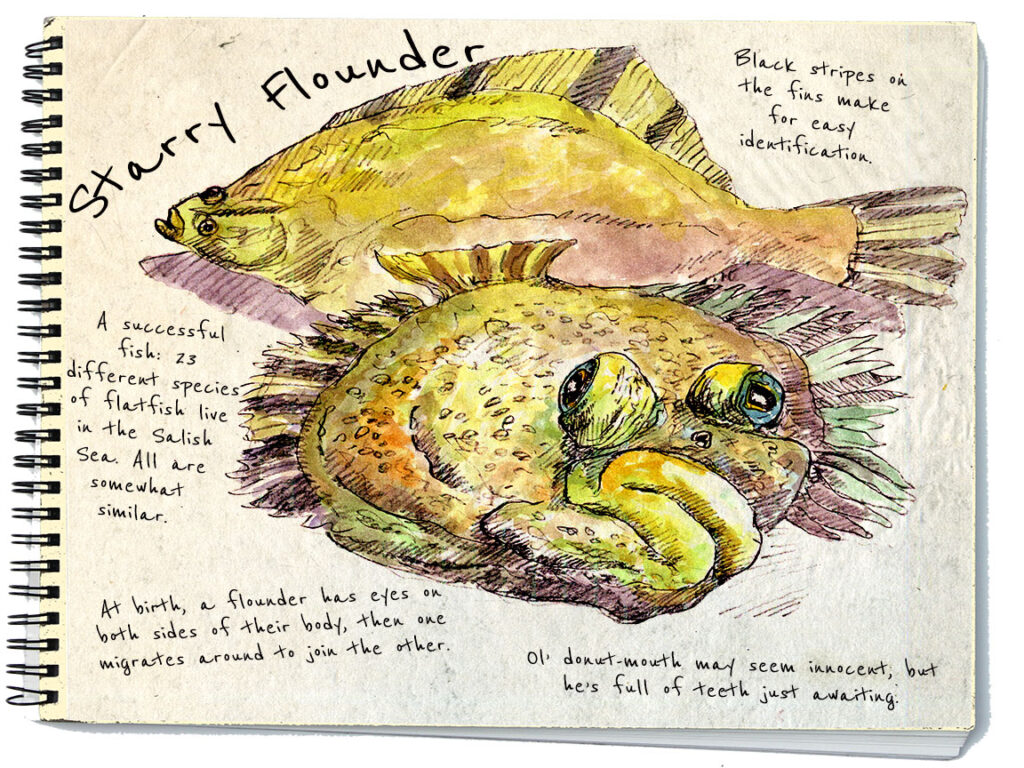

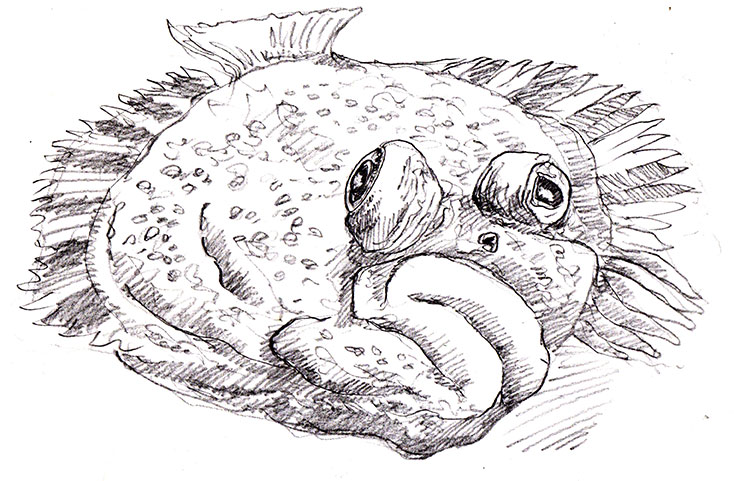

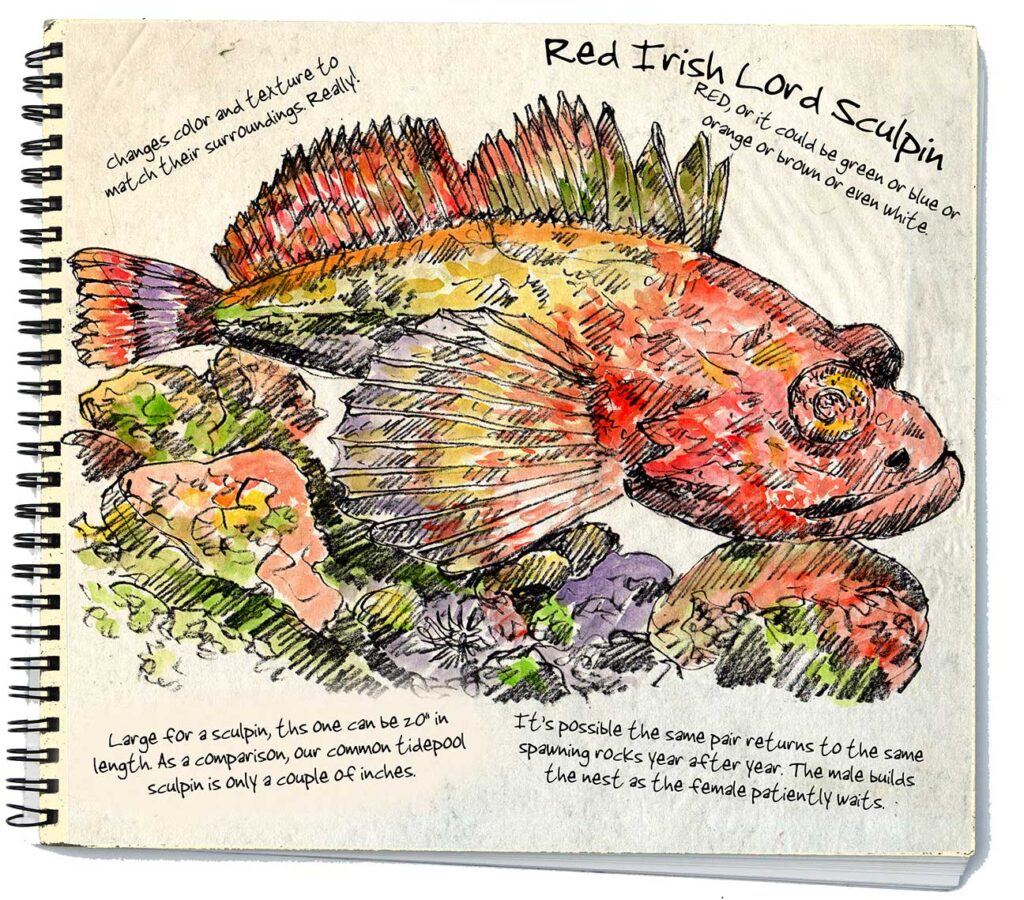

Anemones, whales, worms, birds, urchins, clams, salmon, it’s all been fair game, researched and painted. Time to do another issue? I just go for a sail and there would always be next month’s story.

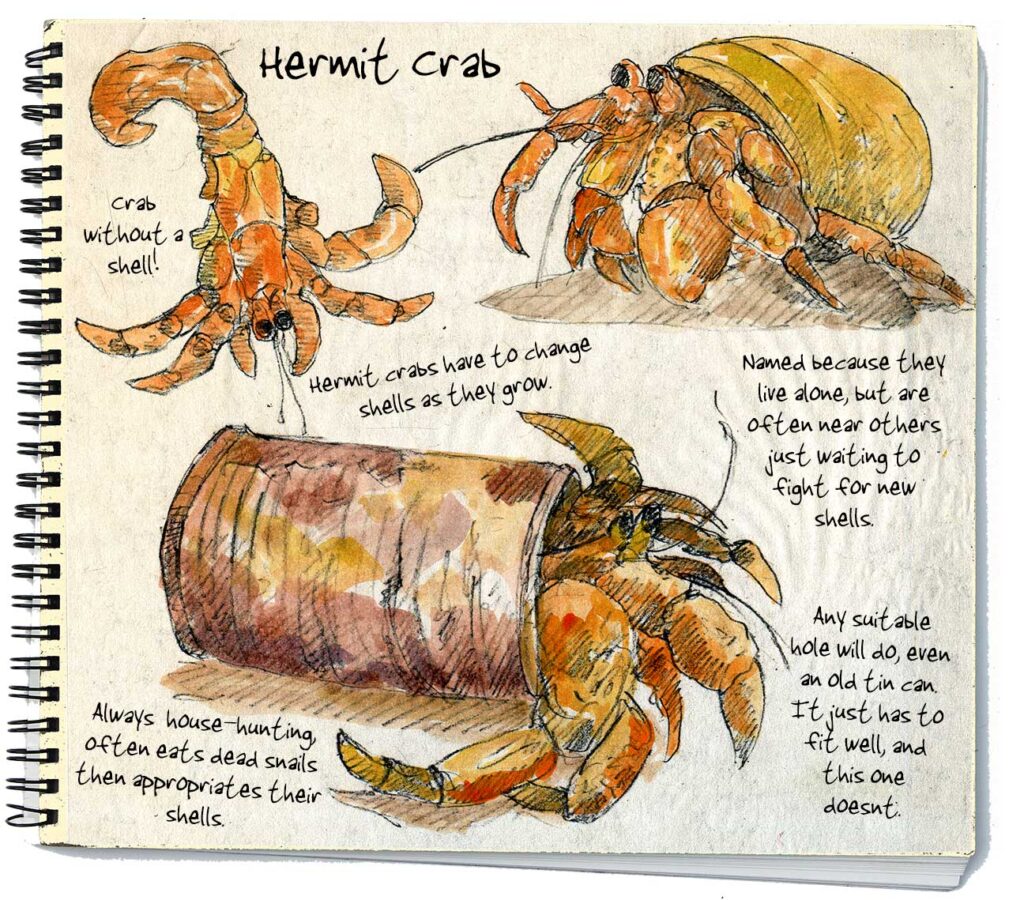

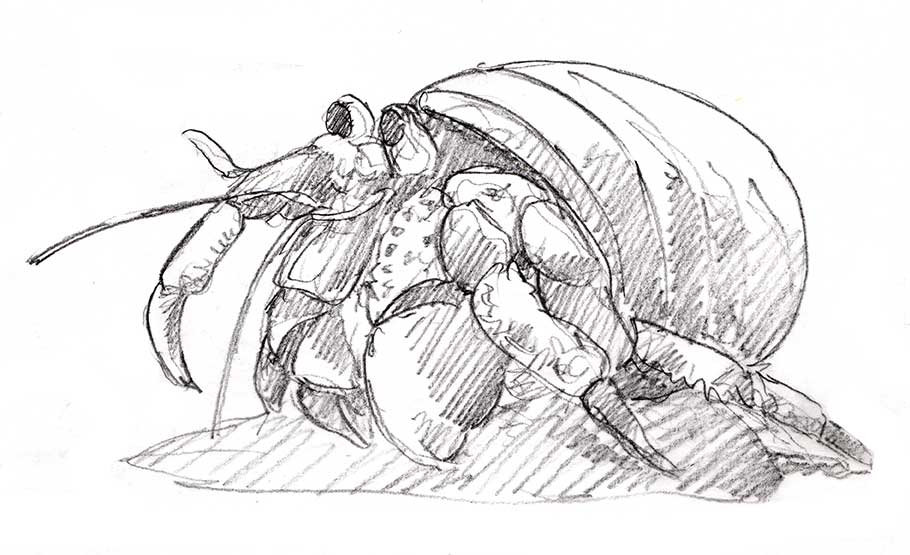

This month, I wrote about this guy, a hermit crab – a crab that borrows other shells to live in. Here were the drawings I did to get it started.

Then it turned into this refined page, and I wrote some text to go with it.

This one will be my last. Time to go in another direction, don’t you think? I mean, really, 118!! And some artist’s claim they need, what, motivation or inspiration to get started?

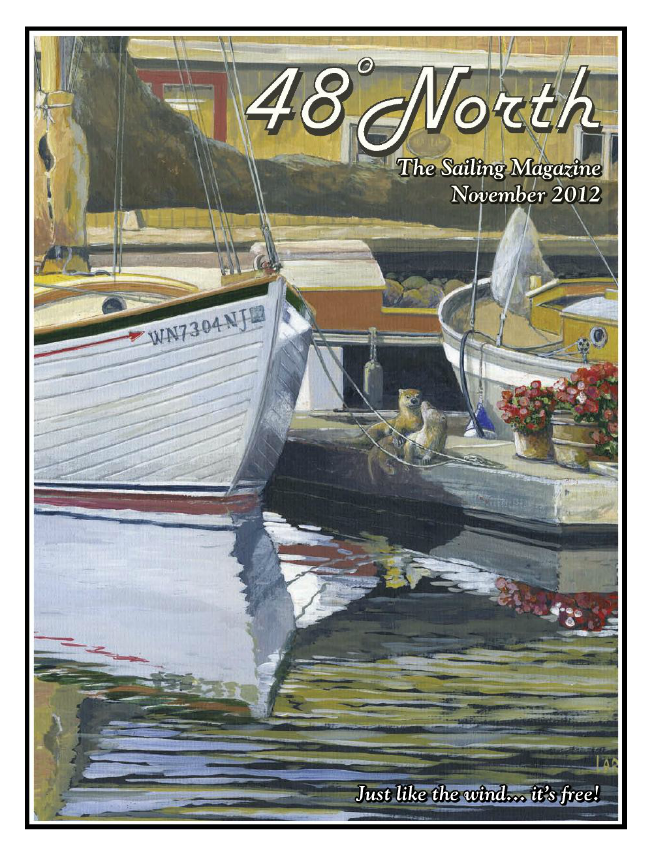

For me, it all started with this issue in 2012. At the time, I had been writing similar stories, but much longer, for 48 North but also the Seattle Times, using my art with the words. It was in that order, write it, then paint it. These sketchbook journals were the opposite. I did the art first.

July 2012-The the first issue.

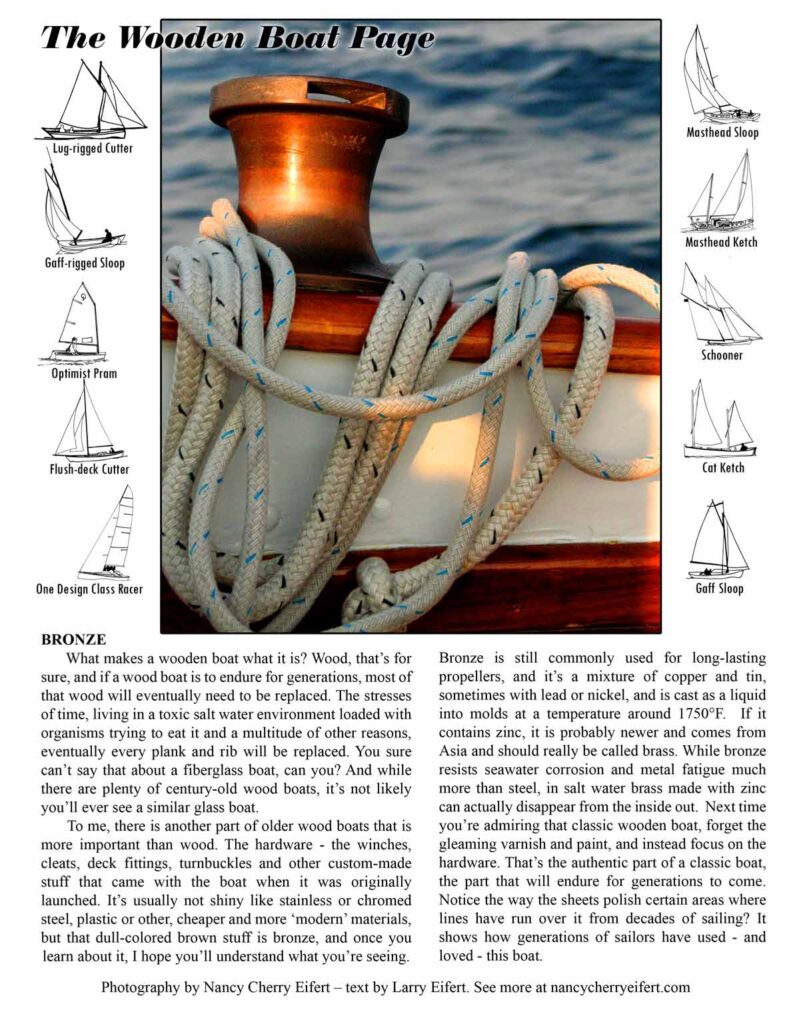

This was a colaboration with Nancy. Her photo, my drawings and words. Our boat!

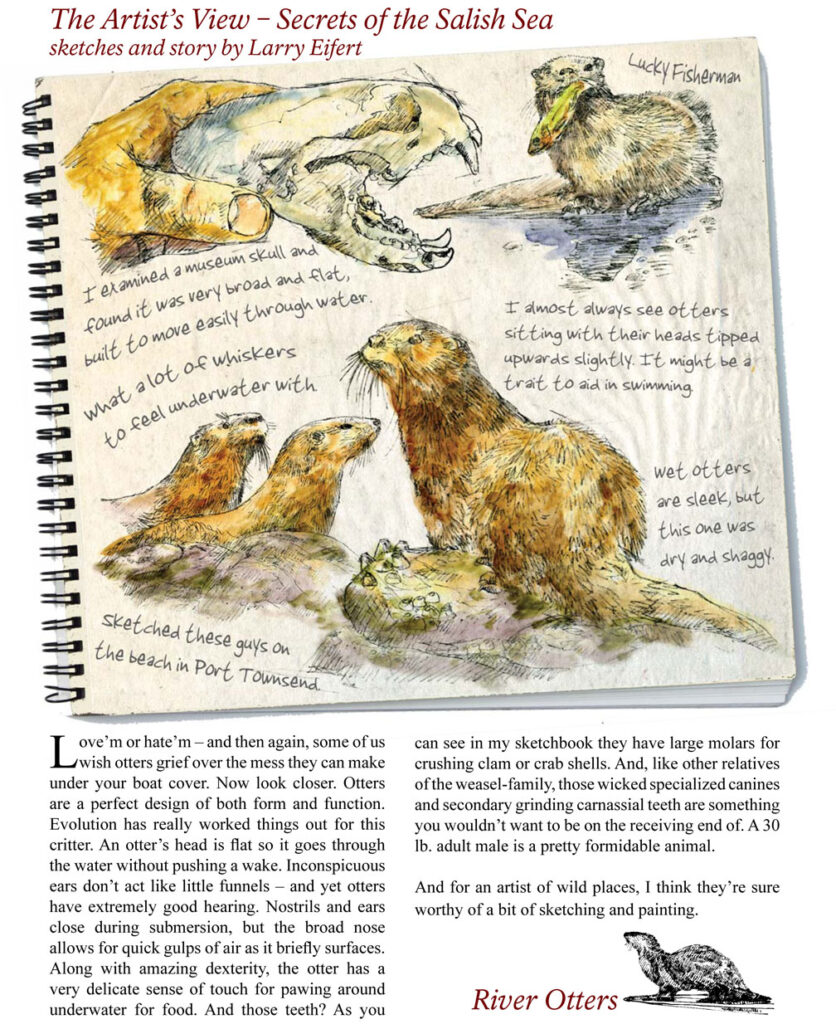

And at the same time, I made a few covers for them. This one of our boat of the left, 1939 Sea Witch, and the otters that were living there as well. We had geraniums on the dock in summer. Locals will probably recognize those other boats, three historic woodies living together. The guy on the right makes high-end violin bows, the black hulled boat belonged to an architect, and us – painters of nature.

So, all these stories can be found here, or almost all 118 of them, on my website.

It’s been fun, but time to move into other types of paintings and writing. Time to explore other ideas and continue on with these huge National Park Service projects – and, boy, are they piled up awaiting.

More soon. Stay tuned. Feel free to pass this around. People seem to enjoy seeing my process.

Thanks for reading this week. You can sign up for emails for these posts on my website at larryeifert.com.

Larry Eifert

Here’s my Facebook fan page. I post lots of other stuff there.

Click here to go to our main website – with jigsaw puzzles, prints, interpretive portfolios and lots of other stuff.

Nancy’s web portfolio of stunning photography and paintings.