Larry Eifert – First published in April 48 North Magazine

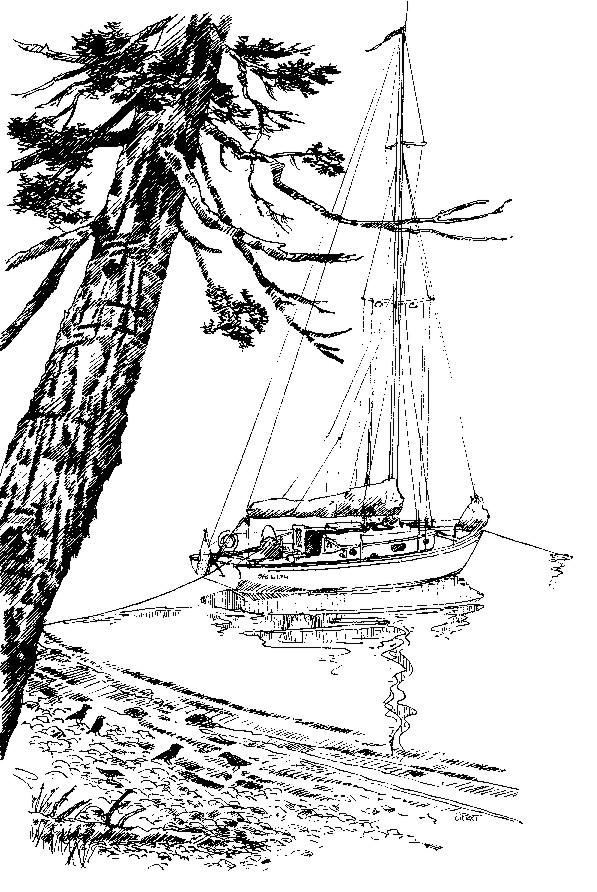

Anchored securely in a little pocket cove, we held Sea Witch’s bow into any possible evening weather with a stern line to shore. Plenty of anchor scope was out, and the stern was firmly tied to an old gnarled Douglas-fir, making our little watery world just about as safe and pleasant as Northwest boating can be. We were fairly close to shore, a hundred feet or so, and the view out the cabin hatch was that of green. Emerald green moss and gray-green lichen, greenish black firs and yellow-green cedar – and green water reflecting it all. Nancy and I spent a very pleasant night of it, playing cards with some red wine beneath the soft glow of kerosene lamps.

Tucked in our bunks early the next morning I was thinking of getting the coffee going when I first heard it, a definite plunk-it right above me on deck. What the heck? Then, there it was again, only now a plunk-it-crack and the sound of something walking. As I slid the hatch open to see, a crow with a shell in its beak flew from the foredeck, heading up to the spreaders for its meal. After consuming breakfast, the crow delicately dropped the shell on the deck and headed back to the beach.

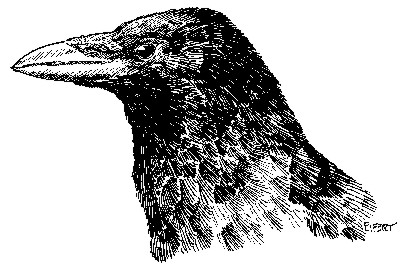

And just how many times have you, too, found bits of broken shell on deck or wedged in a scupper and wondered how it got there? So, here’s the story. Over most of North America, the American Crow, Corvus brachyrhynchos, is a common and familiar bird. No matter where you go, crows can be seen flocking in huge winter gatherings with other “blackbirds.” In spring, they pair off to nest and raise young, often showing up at bird feeders with wing-flapping young in tow. American crows are one of our most ubiquitous birds, but not here in the Pacific Northwest. When you’re in view of saltwater, you probably WON’T see an American Crow. Instead, we have a separate and slightly smaller crow species here, called, what else, the Northwestern Crow, Corvius caurinus. Like American crows, these birds are entirely black with quite striking blue or violet iridescence. And, like ravens and other crows, they have bristles covering the nose.

They also look very similar to the common raven, but are much smaller with a slender bill and tail that is squared off as opposed to the raven’s tail which is rounded.OK, so? What’s the big deal, you ask? Actually, these local crows are pretty interesting. Bird-brained they are not! In fact, their intellect is right up there with your dog, as smart a bird as there is in the world and on par with parrots.Crows and ravens are depicted as being clever and tricky animals in countless American Indian stories and legends, and for good reason. Skillfully, they’ve learned a few tricks that enable them to enjoy the same local seafood that we do.

These birds have learned to pick mollusks at low tide, watching first for a small and shallowly buried bivalve to squirt. They then grab the shell, but the clam, of course, clamps shut immediately so the crow can’t get to the meat, and here’s when the crow’s intellect goes into action. It flies to a rocky beach (or boat deck) where it hovers momentarily before releasing the shell that then crashes down and usually cracks, providing the crow with tasty meal of live clam on the half shell. This trait is evidently learned from adult crows because younger crows usually try this on smaller clams and are much less efficient in opening them. They also do this with nuts and, as one reference states, even snakes, although I’ve not actually seen this.

Northwestern crows are also well known for stashing food for later use. If the pickins’ are good during low tide, birds will store food and then retrieve it later, usually within 24 hours. It also caches food such as bird’s eggs, crabs, and fish; and stores each item in the ground, one at a time and then covers it. And, unlike Clark’s nutcrackers, a western subalpine bird that collects pine nuts, crows actually remember where they put things. (Forgetful nutcrackers, on the other hand, are almost solely responsible for the continuation of pinion pine forests throughout the intermountain west.)

Hiking near-shore trails in the Northwest, we often find many cracked and empty mussel shells far upland in coastal forests, where a crow escaped its brethren for a quiet meal. In this way, each crow helps each shell contribute to the forest’s health, providing needed calcium to plants. It’s a connection between forest and ocean most of us wouldn’t even guess at.

Northwestern crows were first noted by Lewis and Clark on March 3, 1806, at Fort Clatsop, Oregon and later identified as a separate species in 1858. The bird’s range is from Olympia up through British Columbia and into Southeast Alaska, basically any place there’s salt water. Another small population also exists in central coastal Oregon, and, believe it or not, the Audubon Society’s Christmas Bird Count lists a scattered population on the coastal plain of Louisiana near New Orleans.

Why it’s there is anyone’s guess.The northwestern crow usually nests in a vertical fork of either coniferous and deciduous trees, and their nests are made of sturdy sticks lined with moss, grass, leaves, bark, rootlets, hair or even rags. The female lays 4-6 dull blue-green or grayish eggs with brown and gray blotches. Some pairs have crow-helpers that willingly feed and defend nestlings in an unusual cooperative effort. Crow-nannies!

While it was once thought that crows were constantly vigilant because they were on the lookout for hawks or eagles, studies have shown crow vigilance is based more on the opportunity to steal food. The over-riding factor, according to one researcher, is more ‘who’s got food I can steal,’ not ‘is there a predator lurking around. It had been thought that crows are vigilant for predators, but they really are more vigilant about each other’.

Typically, when an eagle flies over a beach, the crows will fly up and mob the eagle until it leaves the area. This is also true with roosting owls attempting to sleep the day away. If you see crows mobbing a tree, look carefully to see if an eagle, hawk or owl is secluded away up there.As we sat in Sea Witch’s cockpit with our morning coffee, I watched the crows walking the nearby beach, swaying side to side in their awkward staggering gate. Sure enough, each one appeared to keep an eye on other crows while the other was on the lookout for a clam breakfast.

Occasionally, one would stop, turn over a stone or piece of eel grass or kelp to check for the shiny gleam of a littleneck or butter clam. Once found, it was doubtful the clam would escape.And knowing this story, the crew aboard Sea Witch enjoyed the breakfast crows not as pests but as truly interesting neighbors. It was an early morning brush with nature at its very best.

***previous*** — ***next***