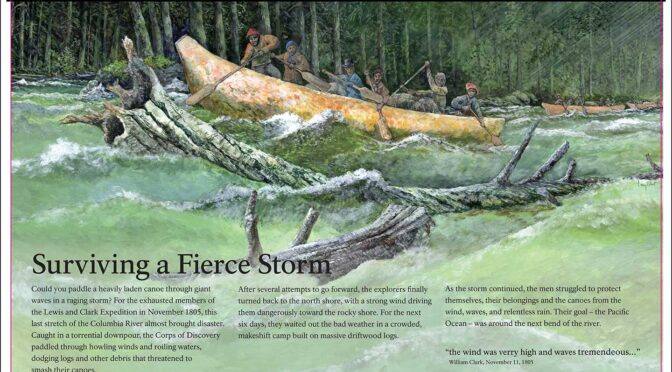

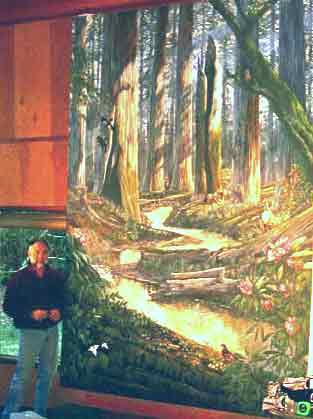

The winding road of life sometimes loops back to the start. In the 1980’s, I was commissioned to paint a mural of Mill Creek in Redwood National Park near Crescent City, California. It was my first piece of public art for any national park, and it opened my eyes to what might be possible for my future. That project made me see the value in painting for a bigger cause than simply art for people’s walls. That idea has remained with me ever sense.

After that first effort, I was soon painting for other parks and some for The Save-the-Redwoods League in San Francisco, which, at that time, was the front line in trying to stop commercial logging of the last 2% of the Coastal Redwoods. That’s right, 2%! I painted a lot of redwoods in those years.

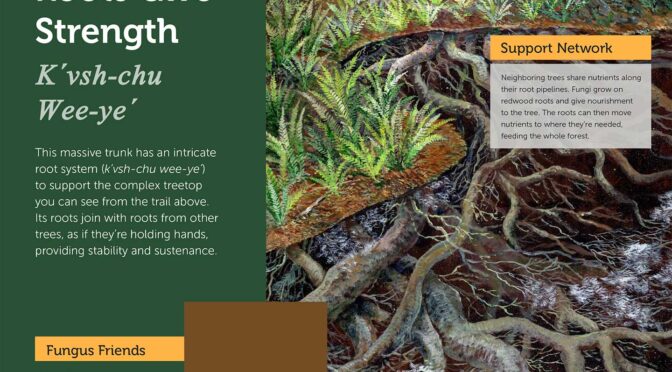

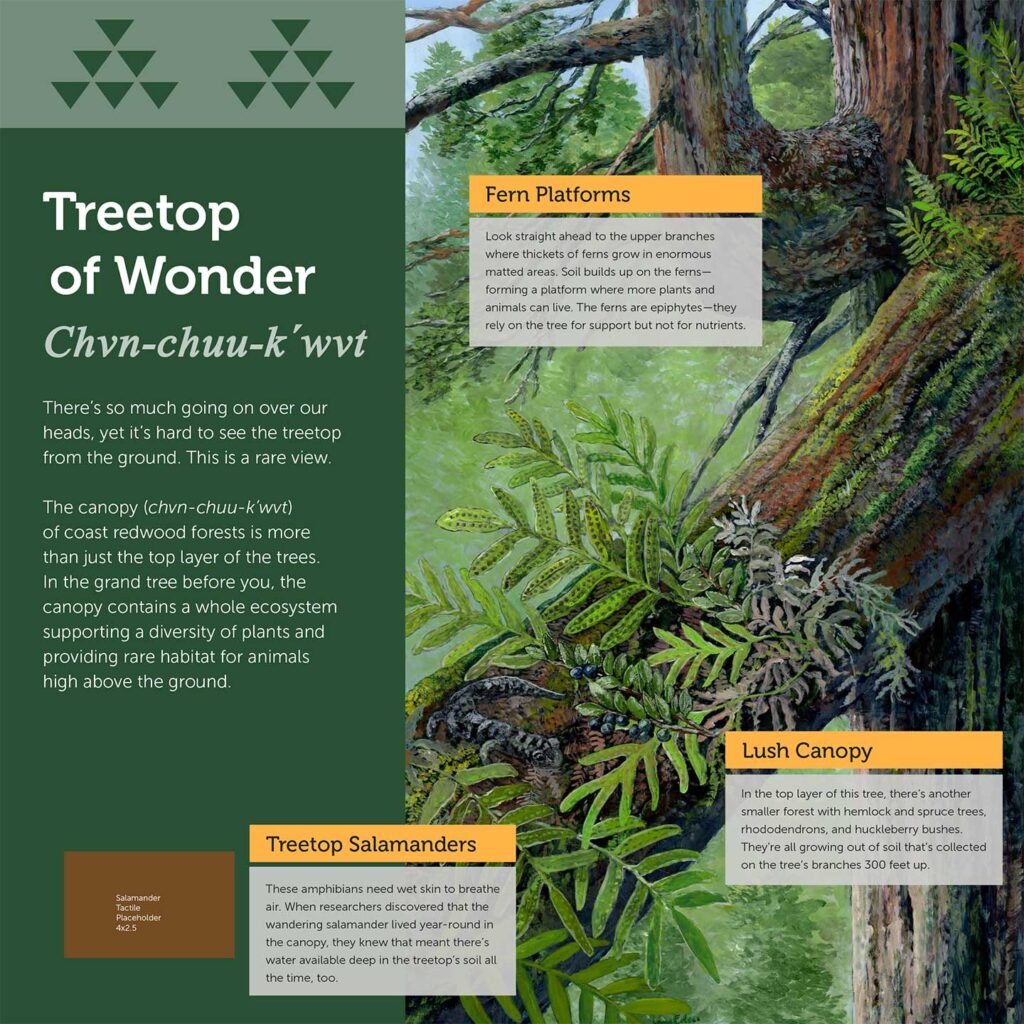

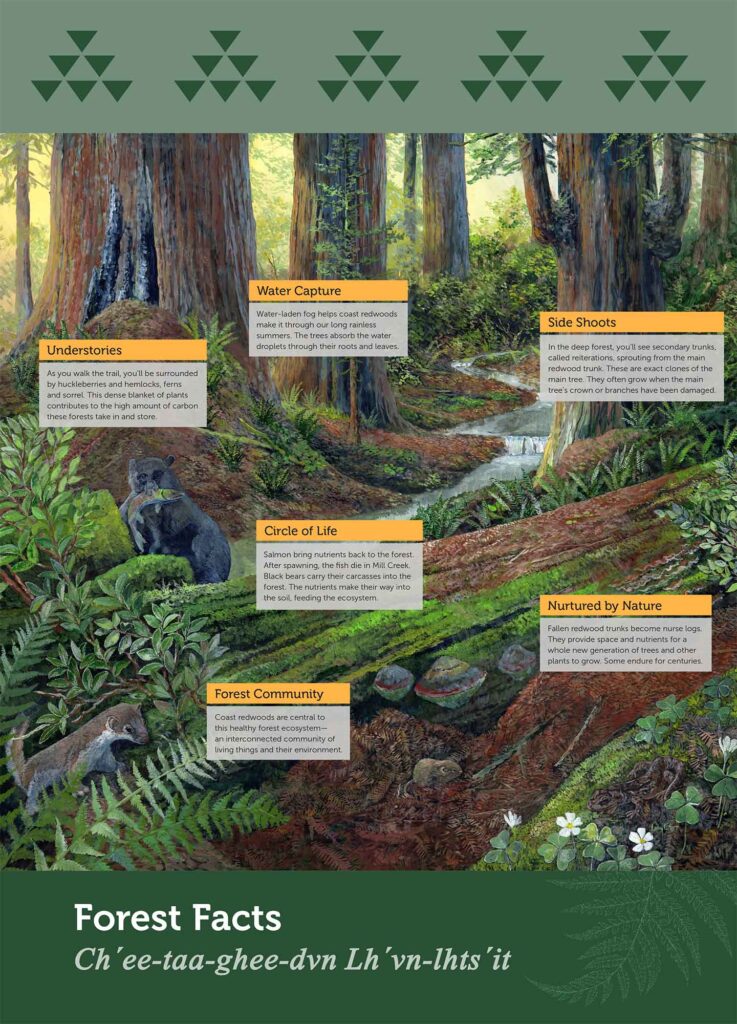

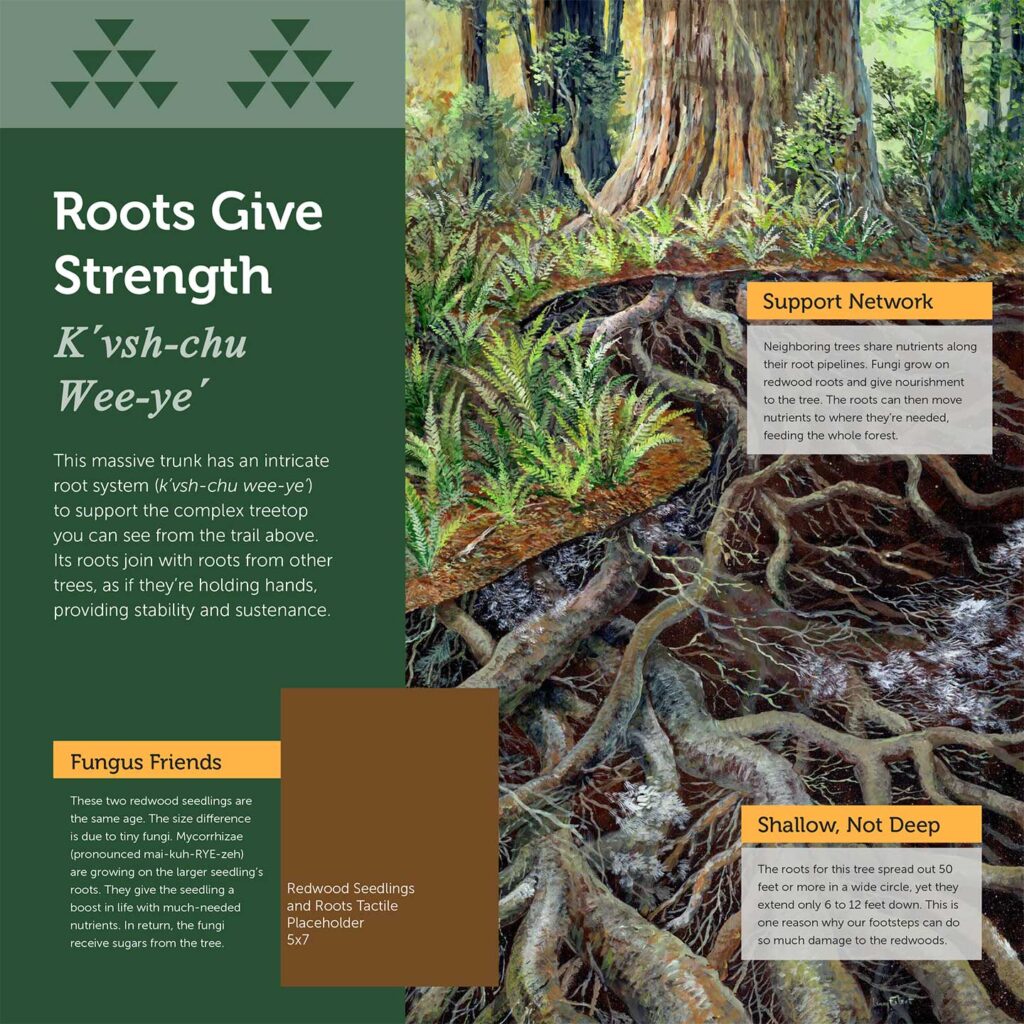

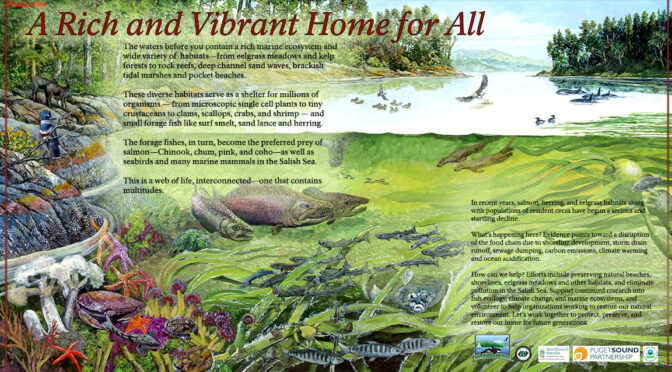

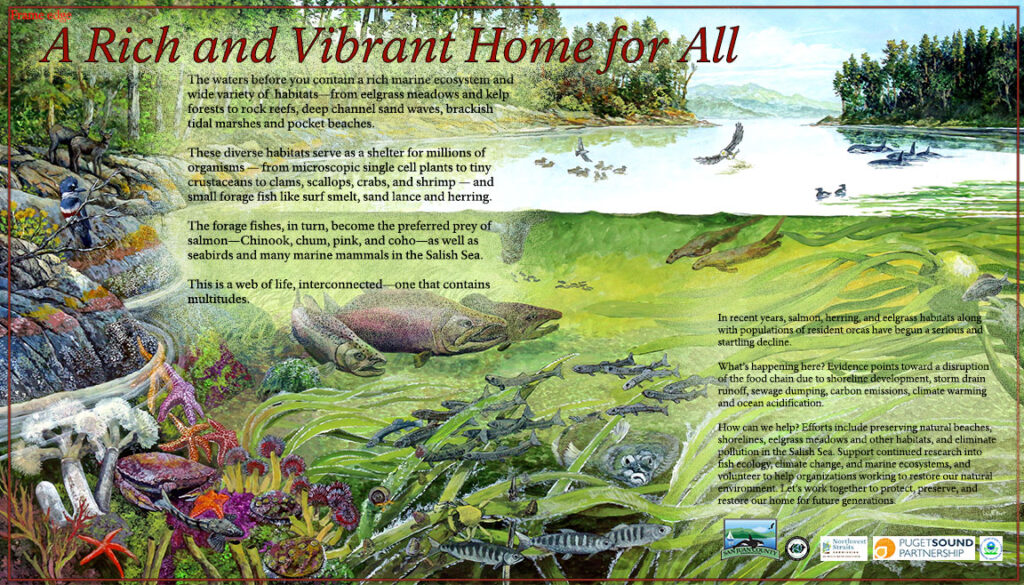

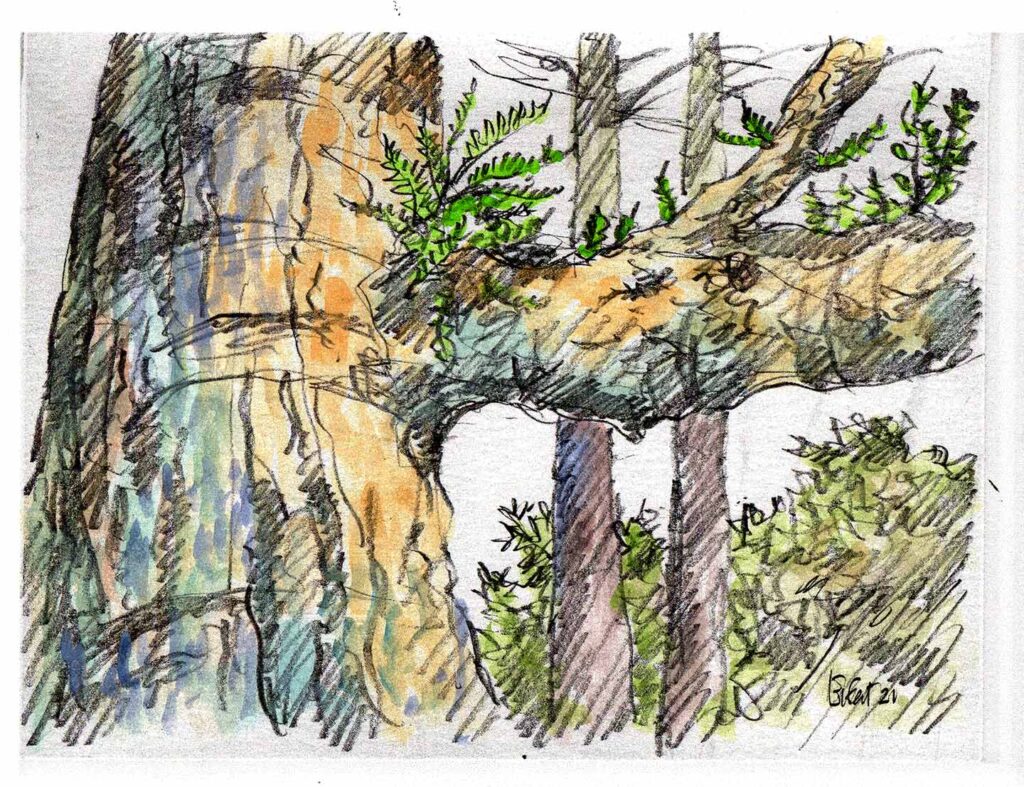

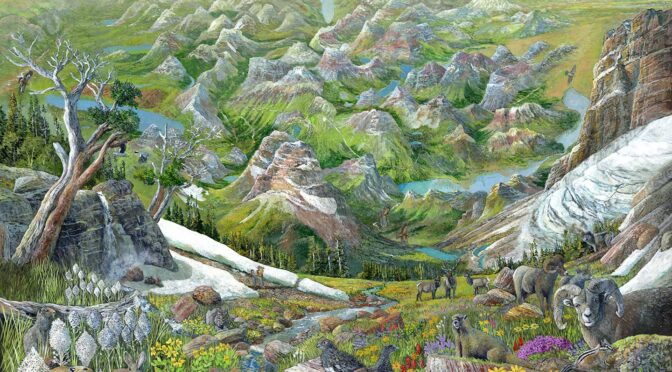

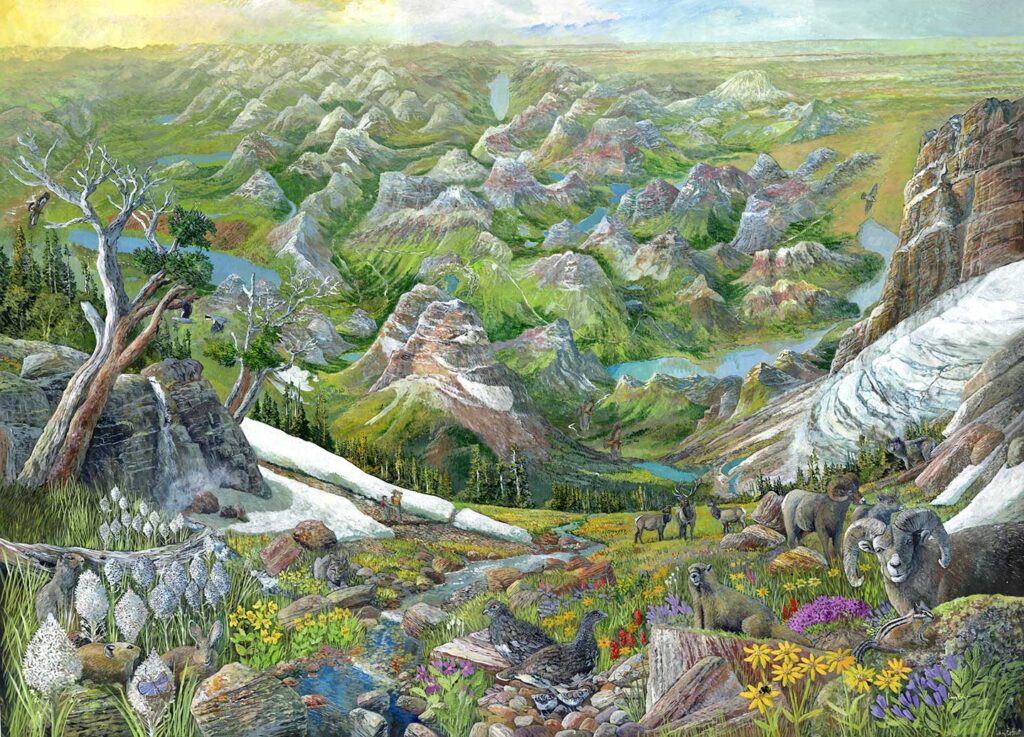

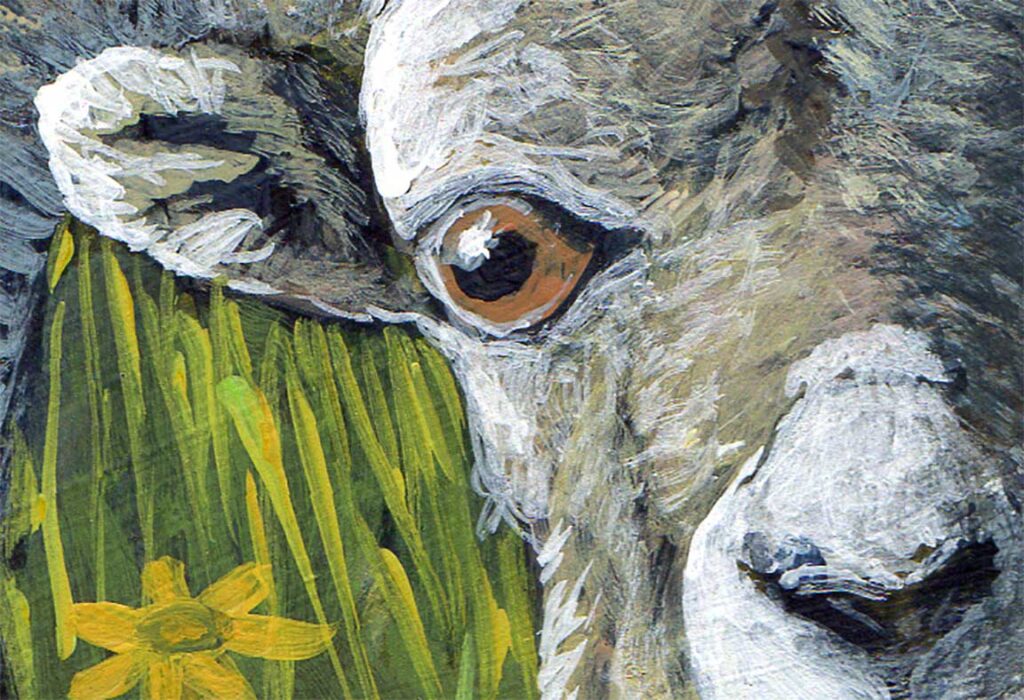

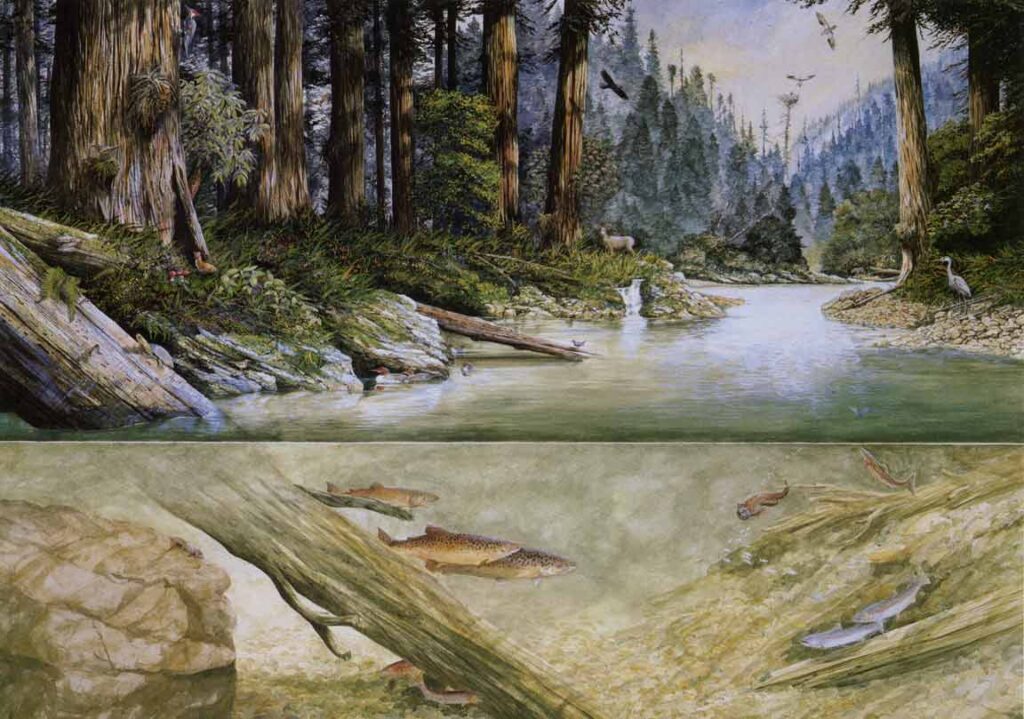

And now, some 40 years later, I was just asked to paint some more redwoods for Redwood National Park. When I did the first painting (seen at the bottom here), no one realized the importance of this area in the Mil Creek Valley of Jed Smith Redwoods State Park. Now we know it’s home to some of the tallest and biggest redwoods on the planet, the Grove of Titans. Save-the-Redwoods League has partnered with Redwood National Park to build a very impressive elevated boardwalk to save the shallow roots of the trees there, and these three new panels with my art will be on that boardwalk. It’s within a few hundred yards of the site of that first painting!

Here’s a reference photo of that grove, you can see similar elements in the big panel at the top. Thanks to the Save-the-Redwoods League for hiring me, and thanks to EDX Exhibits in Seattle for yet another chance to paint nature. Neither of these folks realized my history here, but I somehow got the job anyway! Thanks to Deborah at SRL and Beth and Michael at EDX. You guys are wonderful to work with.

Above is a photo of the Grove of Titans. You can see where I got the design for the larger forest panel.

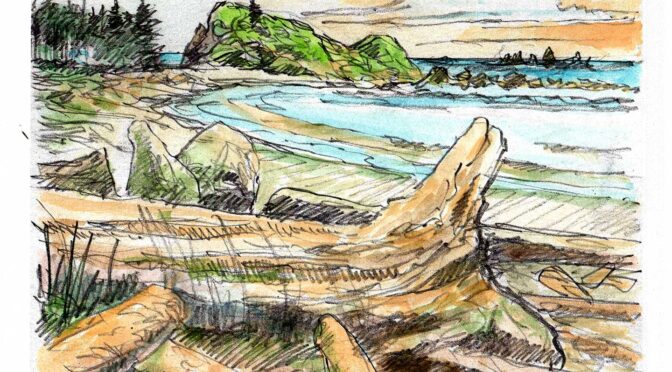

And here’s the original painting of Mill Creek, a watercolor on a full sheet of mat board. I’ve certainly changed my style in 40 years.

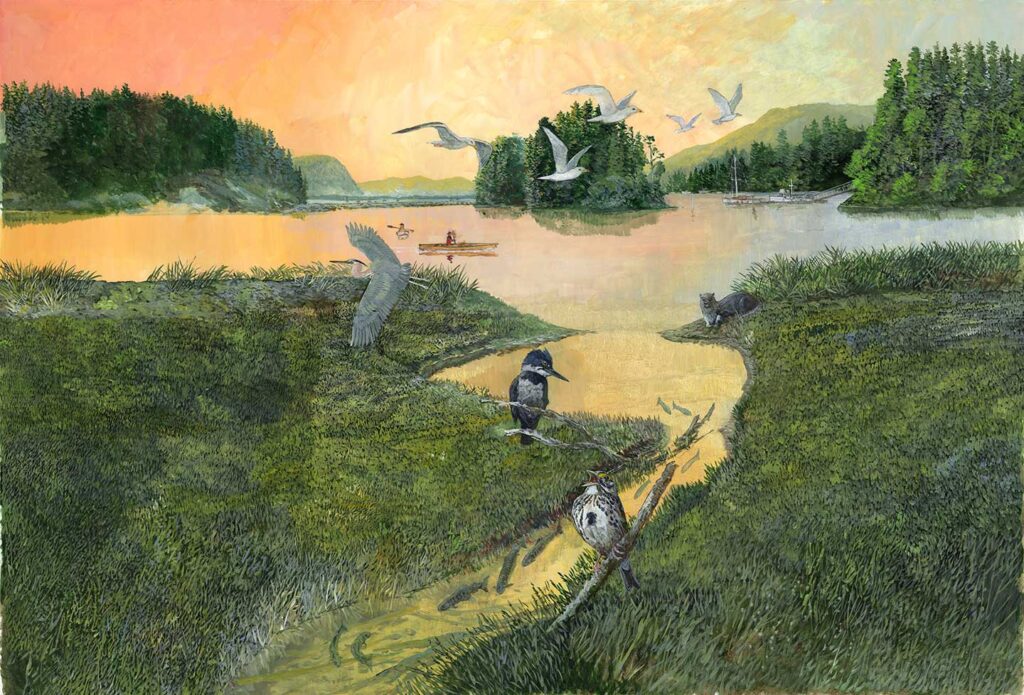

And another painting from that same era of the Smith River that Mill Creek joins. I painted this for Six Rivers National Forest, my first Forest Service piece of art dated about the same time. It was painted for the Discovery Museum in Eureka, CA.

This was a very fun project for me, to go back to my park-roots and remember all these redwood paintings I did in some other life, hundreds of them – at that time, I was the struggling artist.

Thanks for reading this week. You can sign up for emails for these posts on my website at larryeifert.com.

Larry Eifert

Here’s my Facebook fan page. I post lots of other stuff there.

Click here to go to our main website – with jigsaw puzzles, prints, interpretive portfolios and lots of other stuff.

Nancy’s web portfolio of stunning photography and paintings.

And here to go to Virginia Eifert’s website.

[previous title] — [next title]