| by Larry Eifert

Originally published in 48North magazine, February 2009

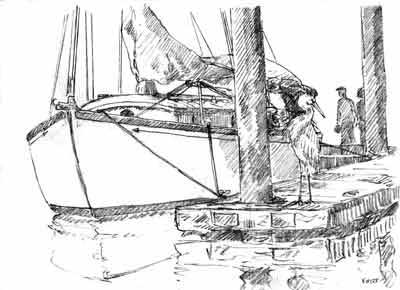

The four-foot tall yard ornament stood on the end of our dock. Focused on its next meal, the great blue heron appeared to be unaware of our presence – completely unaware. In the growing twilight of early evening we hesitated, then stopped and waited, as if we were in a restaurant and a previous patron hadn’t yet finished their meal. And still the heron didn’t move. It’s interesting how, when you’re in a ‘nature moment’ like this, all your senses seem heightened. I heard the drip, drip, drip of a leaky water outlet nearby. Then a distant truck downshifted. Gulls and crows appeared to be having some sort of dispute over by the breakwater, or at least that’s what it sounded like, and I could hear low murmurs of someone doing a radio check on their boat. And still the heron didn’t move. Then, as smoothly as if it were liquid, it lowered its long curved neck towards the water, slowed its motion, and, wham, it came up with a small fish ‘barbeque tong’ style held between that long beak. The fish was wildly flapping back and forth, but with a quick flip to orientate the scales to the correct direction, the fish became dinner. It was at that point that the great blue noticed us, and with great croaking noises it spread those huge wings and flew down the channel. Wow, I think is what Nancy said under her breath! Wow, indeed.

These birds, the largest herons in North America, are known to every sailor who ever walked a dock in the Northwest, and it’s probably fair to say that, if you haven’t had a “heron experience,” you’re not a sailor!

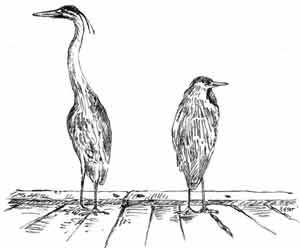

Great blue herons are well adapted for life here in Puget Sound and other shallow salt or freshwater locations from Southeast Alaska to South America. Some have even made it to theGalapagos Islands. Fishermen often do well with leg waders and long poles – and these birds have both in abundance. With wingspans of 71 inches (that’s almost six feet or two meters) it’s amazing this large bird only weighs 4.8 to 8 lbs. (2.2 to 3.6kg). Why this is so is because, like many birds, flight is easier with hollow bones. And these herons are actually much smaller in body mass than they appear – there’s a lot of feathers there. Years ago, after a winter storm, I found a great blue that had been blown out of a tree and was pretty banged up. I tossed my coat over it, gathered up the frightened and rumbled mass of feathers and headed for the car, only to find a snake neck burrowing its way out from beneath my arms and aiming that needle-sharp beak directly for my eyes. It clearly knew what it was doing, aiming to disarm first and then escape my clutches. I grabbed the neck, only to realize I was dealing with a force not unlike arm wrestling a bodybuilder. Honestly it was all I could do to stabilize the situation. The heron survived, and so did I, but it was a lesson in the strength of the neck muscles of these birds.

Herons often nest in loose groups, using waterside trees, usually choosing red-alders over 75 feet tall. These avian condominiums are called “heronries,” and each breeding pair build a large stick nest where the female lays three to six pale blue eggs. After a month of nest sitting, which, for me is difficult to imagine how a bird with stilts for legs can accomplish, both parents share in feeding duties by regurgitating food they’ve previously caught. Yah, I know, but think of warm pabulum and you can’t be far off. We’ve all been there. In fact, this stuff might be better than what we got because great blue herons eat small fish, shellfish, amphibians and even small birds. Let’s see, that’s like a meal of mushy tilapia, prawns, frog’s legs and squab. Not so bad.

As most marina people know, great blue herons don’t migrate with the coming of winter. They’ve adapted to winter here, foraging in eelgrass beds at low tide or hunting small voles or mice in fields when there aren’t any fish. After winter storms, great blues are often seen stalking prey in wet meadows where heavy rains have forced rodents from underground tunnels. They locate their food by sight and usually swallow it whole (without teeth, it’s difficult to do otherwise) and have been know to choke on meals that are too large (where a comparison to us might again be appropriate).

What ISN’T like us is this crazy neck the great blue has developed. There are special vertebrae in that long tube that create an “s” shape, allowing the neck to actually curl like a spring prior to attacking its prey. It does double-duty by also allowing herons to fold their necks when flying, an important feature in cutting air resistance and saving flight energy. This isn’t always seen in marinas where herons often fly with their necks extended. It’s a dangerous forest of masts, halyards, shrouds and stays out there and a heron needs all the three dimensional visual help it can get.

Herons depend on small fish, but also on clean water in which to find them. They depend on eel grass beds where small fish spend time growing up. They also depend on US, fellow boaters, to provide them with what they used to have plenty of, namely clean water and a healthy Puget Sound. And without a healthy Puget Sound, without lots of small fish to eat, it’s goodbye great blue heron. When you’re walking your dock, ask yourself this: “have I seen any small fish here recently, or, have I seen a great blue heron fishing for them?” If not, then why not? This stuff isn’t rocket science, you know. This is our home, and it’s also the great blue’s home. We need to make sure these spectacular birds are getting what they need to continue to live here. If they aren’t – then we are the losers too. Having that great blue on the end of our dock tells me that, at least for now, my marina still provides this bird with what it needs. It’s like a gauge, something I can measure against future evenings in future years. It’s also a measure of the quality of life that, to me, is very important.

***previous*** — ***next***

|