| by Larry Eifert

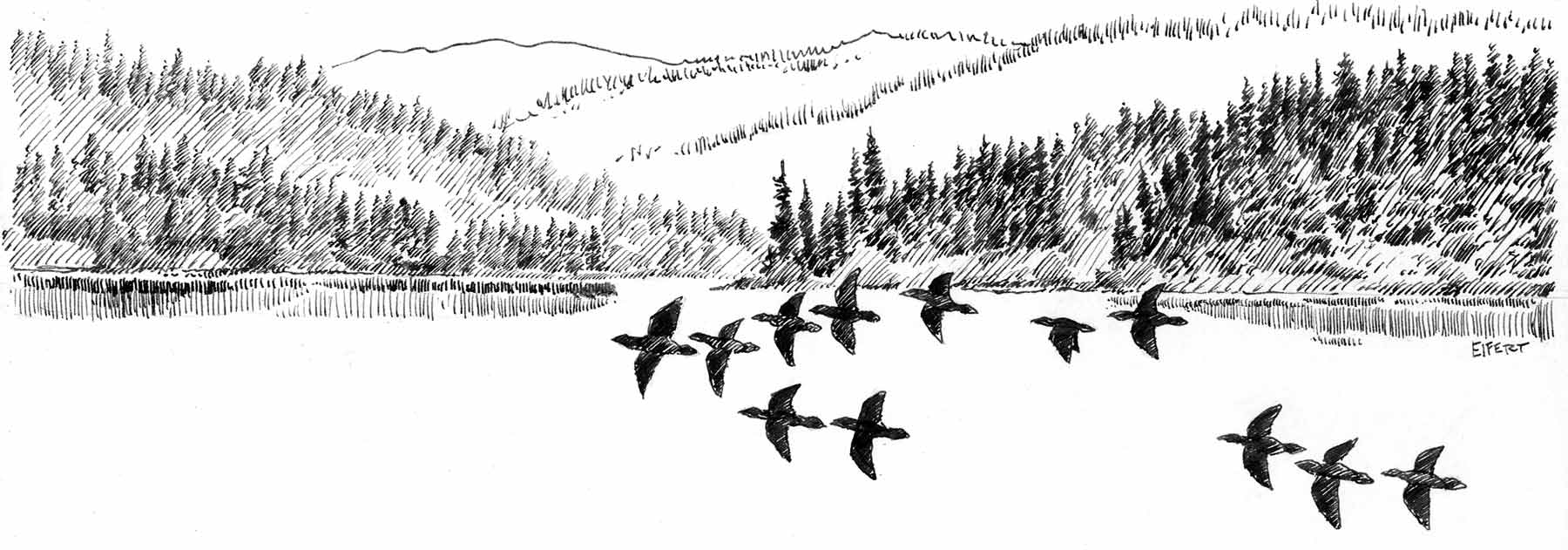

Originally published in 48North magazine, February 2008

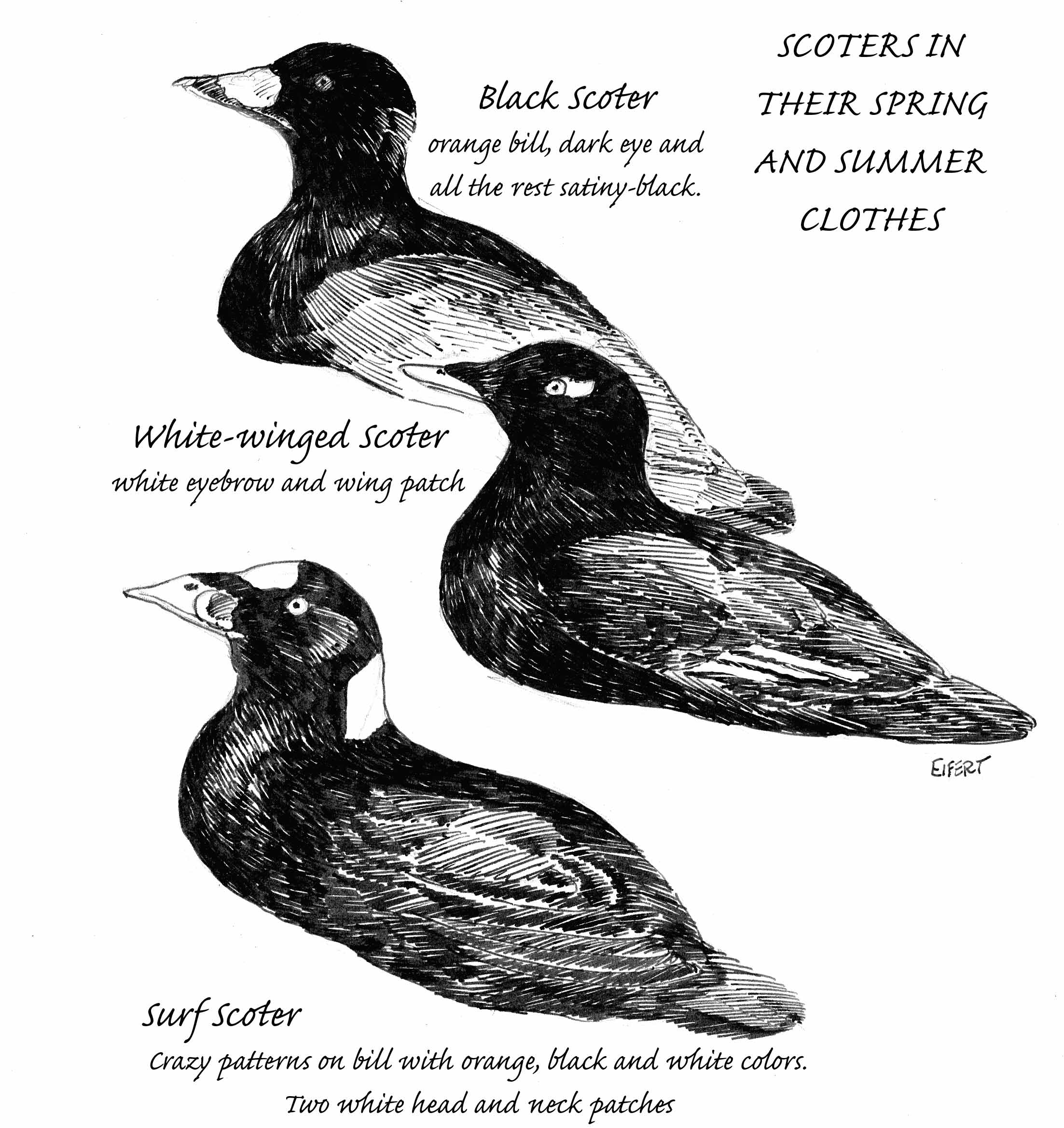

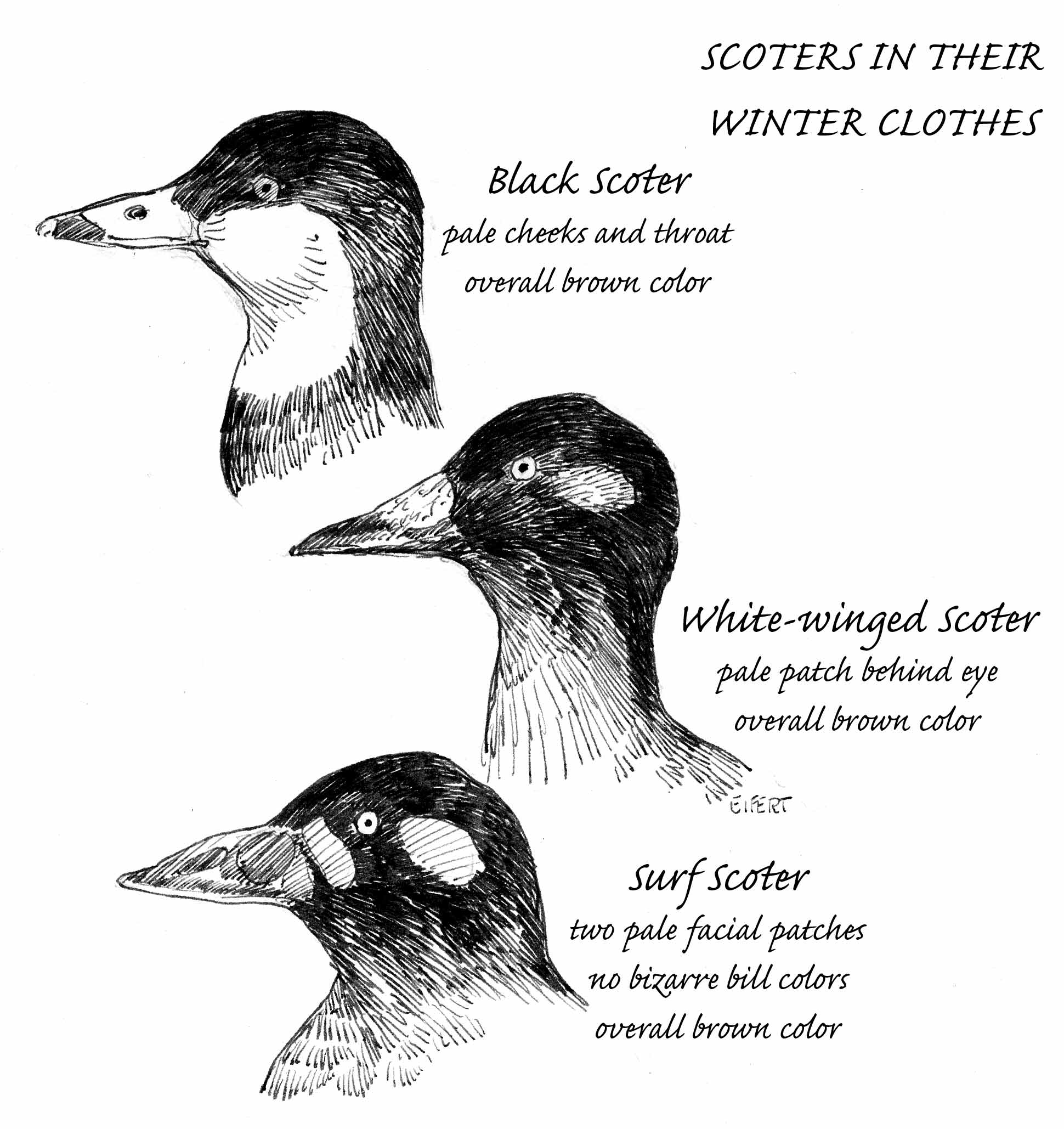

Goggle-nose, Plaster-bill, Horse-head Coot, Blossom-bill, Snuff-taker, Bottle-nosed Diver and Mussel Bill are some of the names I’ve heard for these birds. This wasn’t a big flock, by any measure, but it was just good to see these birds at all. The six or so black seaducks drifted together in a line, just where two tidal currents joined. They dove together as a unit and, after thirty seconds or so, surfaced in almost the same spot. It was fun to watch, but I couldn’t figure what they were going for. Too early for herring eggs on eel grass and this was probably too deep for eelgrass anyway. I assumed they were fishing for some of the many crustaceans or shellfish that are another part of their diet. These were scoters, pronounced sk-o-ter and they have a story we haven’t really figured out yet. Scoters fly in loose ‘v’ formations. They’re heavy birds that need a good running start to become airborne. Stocky, short-necked dark-colored diving birds, scoters breed in the far north and winter here in Puget Sound, although some non-breeding adults remain here all year. There are actually three separate but similar species and their common names are surf, black and white-winged scoters. In spring, breeding pairs fly north to the tundra of Alaska andCanada, where they build ground nests at the edge of lakes and rivers. Scoters have a high preference for their original breeding, molting and wintering areas, so once populations crash in an area they are slow to recover. With a life-cycle geared for adult survival, they don’t even breed until at least two years of age, and don’t breed at all in some seasons. Like other waterfowl, they have a molt each year when they completely loose their flight feathers and are grounded for a month. Flashy spring colors for our three scoters. All three scoters are about 20” long, bill to tail. Surf scoters are among the least studied water birds in America. Named for their skill of foraging in surf, the scientific name perspicillata means spectacular or conspicuous, referring to the bizarre, multicolored bill. This looks massive and even swollen on the sides with a distinct Roman nose appearance. The problem is, since 1979, the number of scoters on Puget Sound has dropped by 50% or more, and some scientists speculate that contaminated shellfish may be causing the decline. Puget Sound once attracted some of the largest wintering scoter populations on the West Coast, but here are some sobering facts about our watery neighborhood friends. Nineteen of the thirty most common marine bird species in northern Puget Sound decreased by 20% or more between 1978 and 2004. Since 1979, the total number of marine birds in the Puget Sound region has dropped 47%. Another once-common bird, the western grebe, has had population declines of 95 percent over the last 20 years. Scoters dull down for winter, when we often see them here in Puget Sound. A larger number of surf scoters winter near the San Juan Islands and on southern Puget Sound in Budd and Eld inlets. To make matters worse, the people who should know about this do not yet fully understand what’s driving these declines, although, to me, it’s not difficult to guess at. Here’s my personal view of what’s going on – and you’ve probably heard it all before. Of course there is habitat loss, hunting (nationwide, 80,000 scoters are shot each year), by-catch from fishing operations (including derelict fishing gear) that have taken their food, and harm to breeding grounds in the Arctic where many of scoters nest. To put it mildly, life isn’t very easy for most birds these days. Some problems are tiny but in our grasp to fix, and it sounds like: “drip, drip, drip” one drop at a time. As oil drips from old car engines around Puget Sound, it washes into our creeks, rivers and storm drains. Eventually, this all goop ends up in bays and estuaries, and all the other salt water hereabouts. Outdated boat engines pass many gallons more out their exhausts. Added up, each year more oil is flushed into our local salt water than HALF the Exxon Valdez spill (P-I Dec.1, 2007). Common herbicides and pesticides, like Roundup, Weed and Feed or the other nearly-endless list of other toxics we put on our lawns or gardens also gets flushed into storm drains and eventually into saltwater. Shellfish are filter-feeders and it’s a toxic stew that mussels consume, one drop at a time.. They pump water through their bodies, then filter out and keep the solid stuff – food, yes, but also the toxics. In turn, larger critters like scoters consume them. How many? Well, on the west coast of Vancouver Island, a surf scoter’s stomach was dissected and found to contain 1100 blue mussels – in ONE scoter, not a flock. (Blue mussels are about 30% of the surf scoter’s diet.) Black and white illustrations don’t show the surf scoter’s amazingly-colorful bill, but when you see the reddish-orange, yellow, black and white colors contrast with the rest of the all-black body, it’s quite a sight. What can you do to help these birds? Looked under your car lately? Still use herbicides or pesticides? We don’t, and we have an acre of lawn that looks just great, not to mention the organic flower and veggie garden. It takes a bit of work, but so does spreading or dripping all that poison (not to mention the money it costs you to buy it). In the end, it’s not about helping the birds so much as it is helping all of us maintain the place we call Home. If scoters are dying, who’s next? ***previous*** — ***next*** |