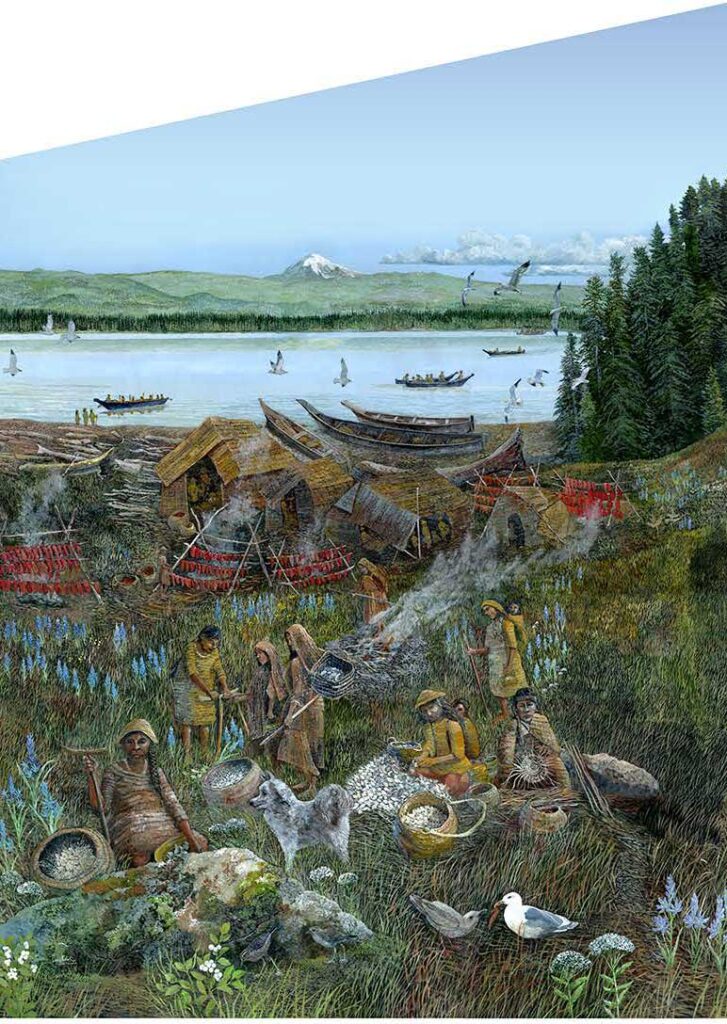

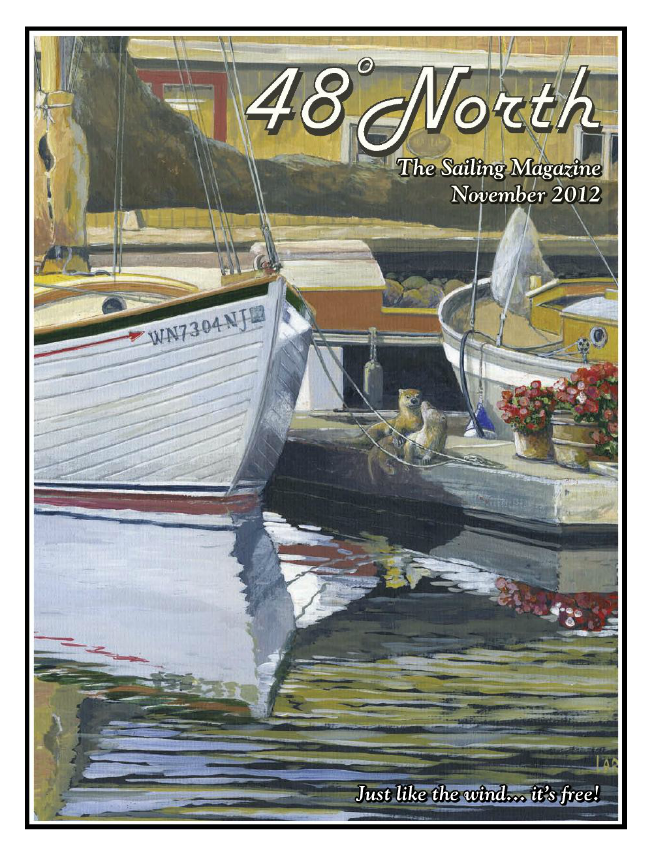

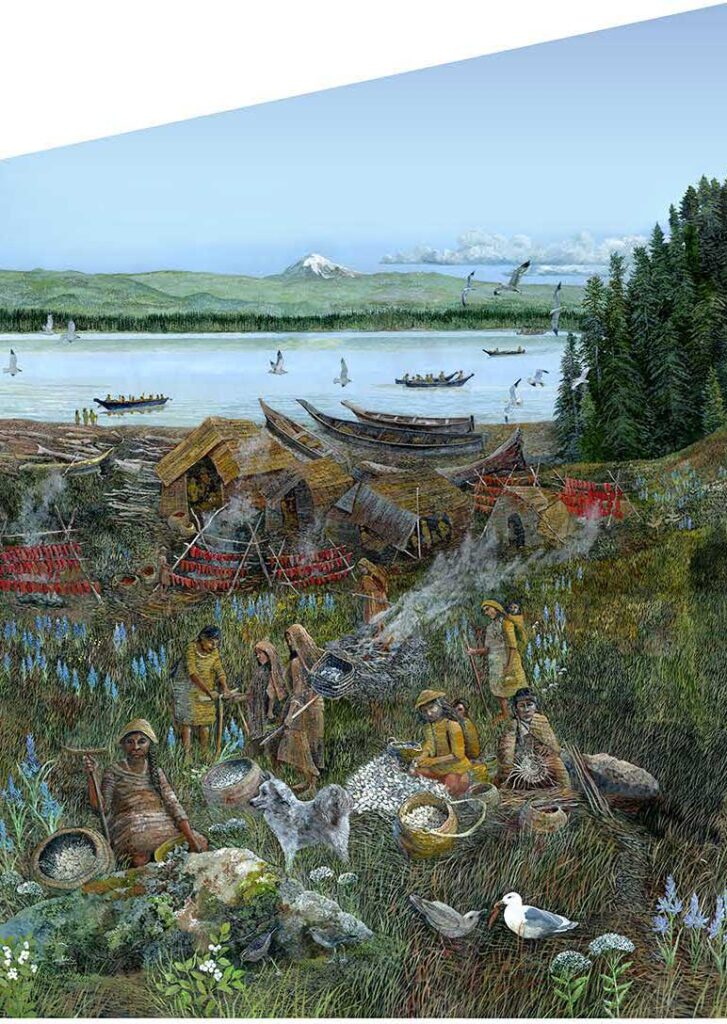

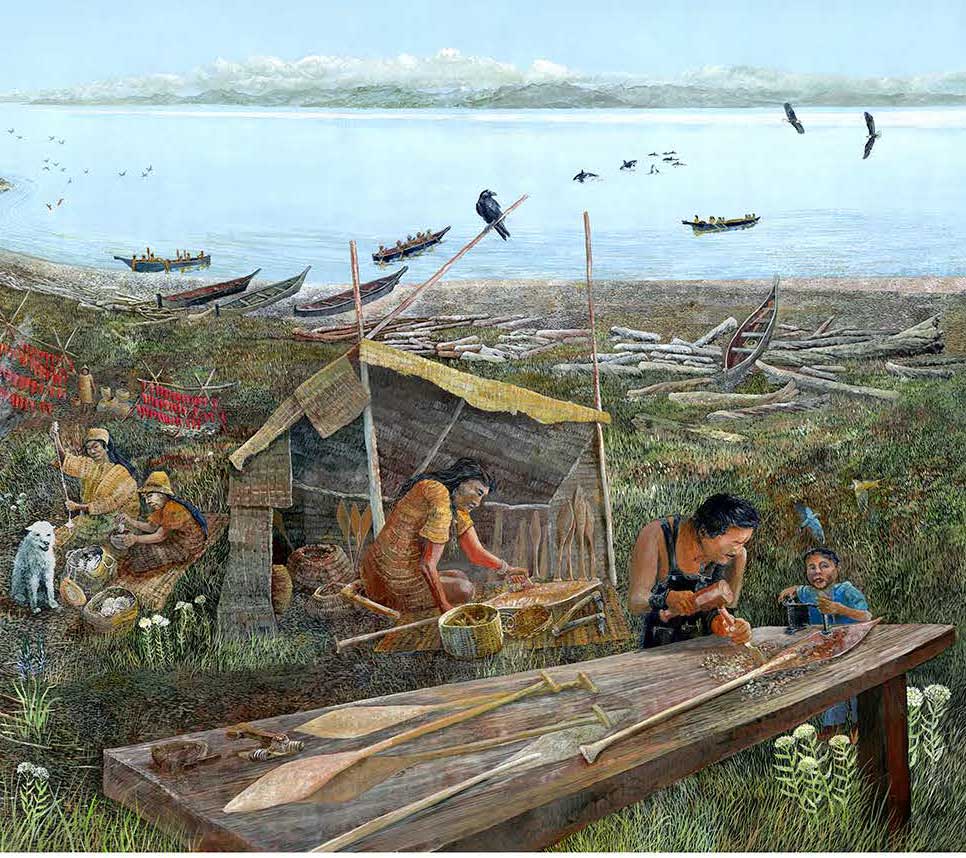

I’ve been painting some outdoor wayside panels for the City of Everett, Washington. This is my 3rd and 4th for Everett, which is north of Seattle and is becoming a real city with some real money to spend on this stuff. But it’s also becoming a ‘real city’, with its nature gone. They have a small nature park in the middle of it and so I’m working on some installations that tell about its nature. Lots of shrub plantings are going on here, putting the place back to some assembly of a native forest.

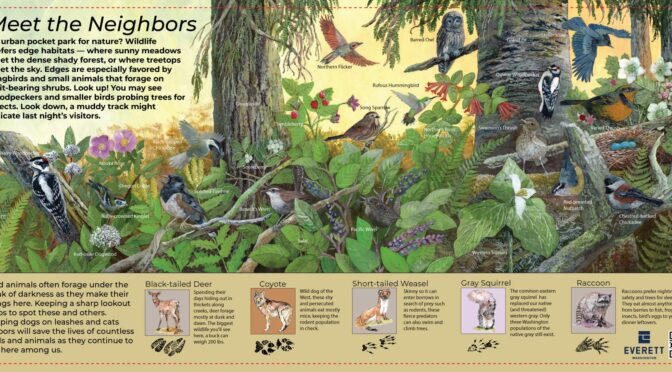

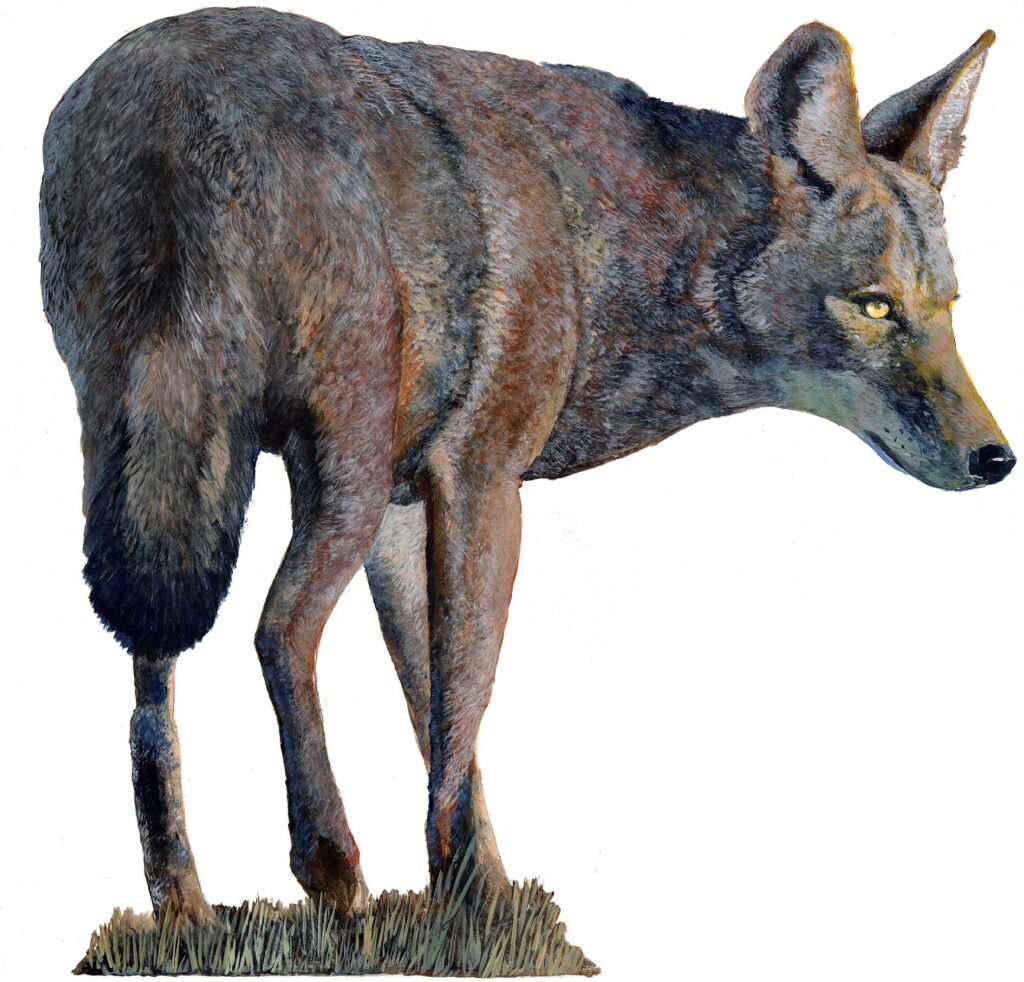

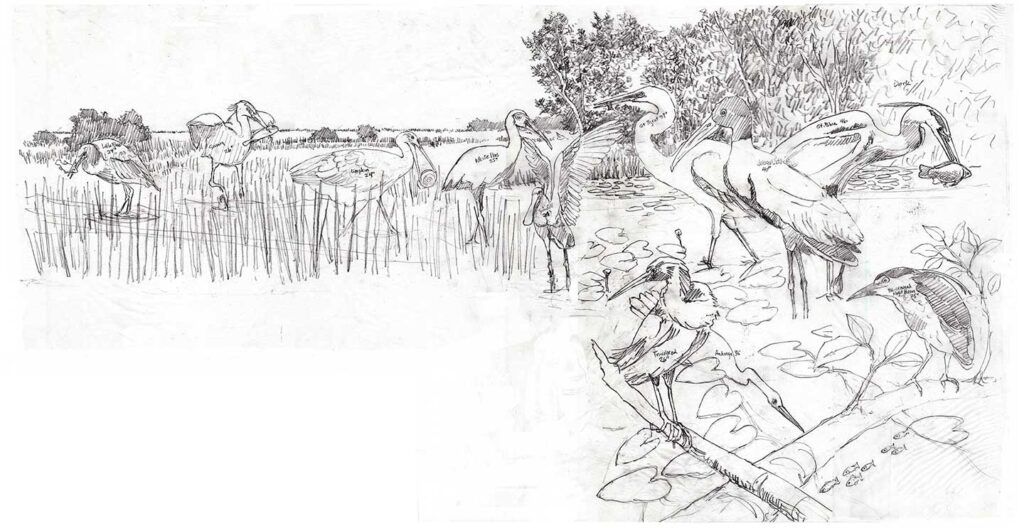

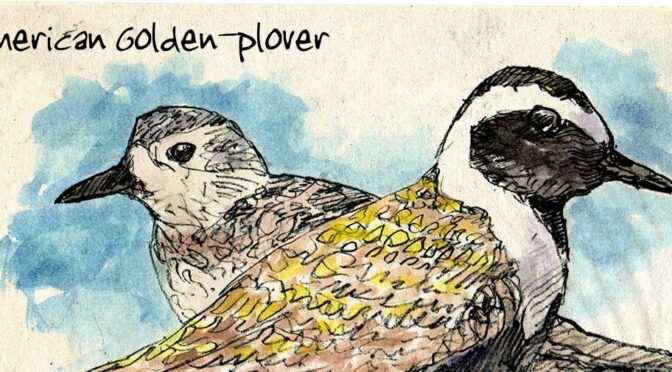

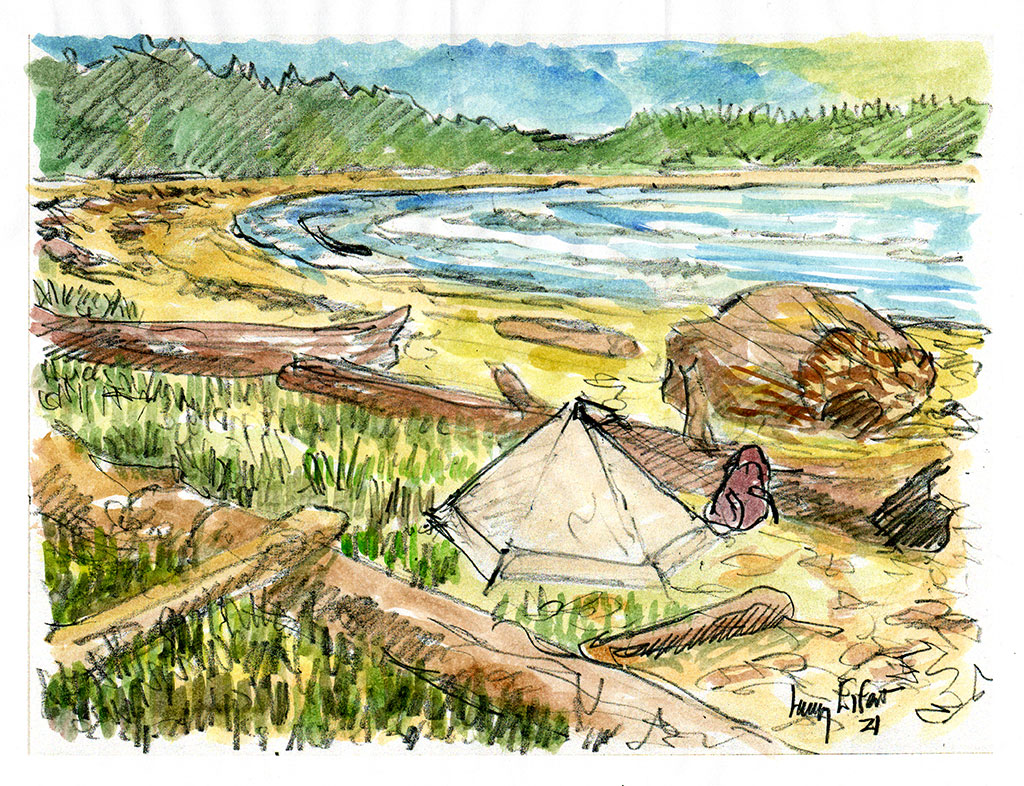

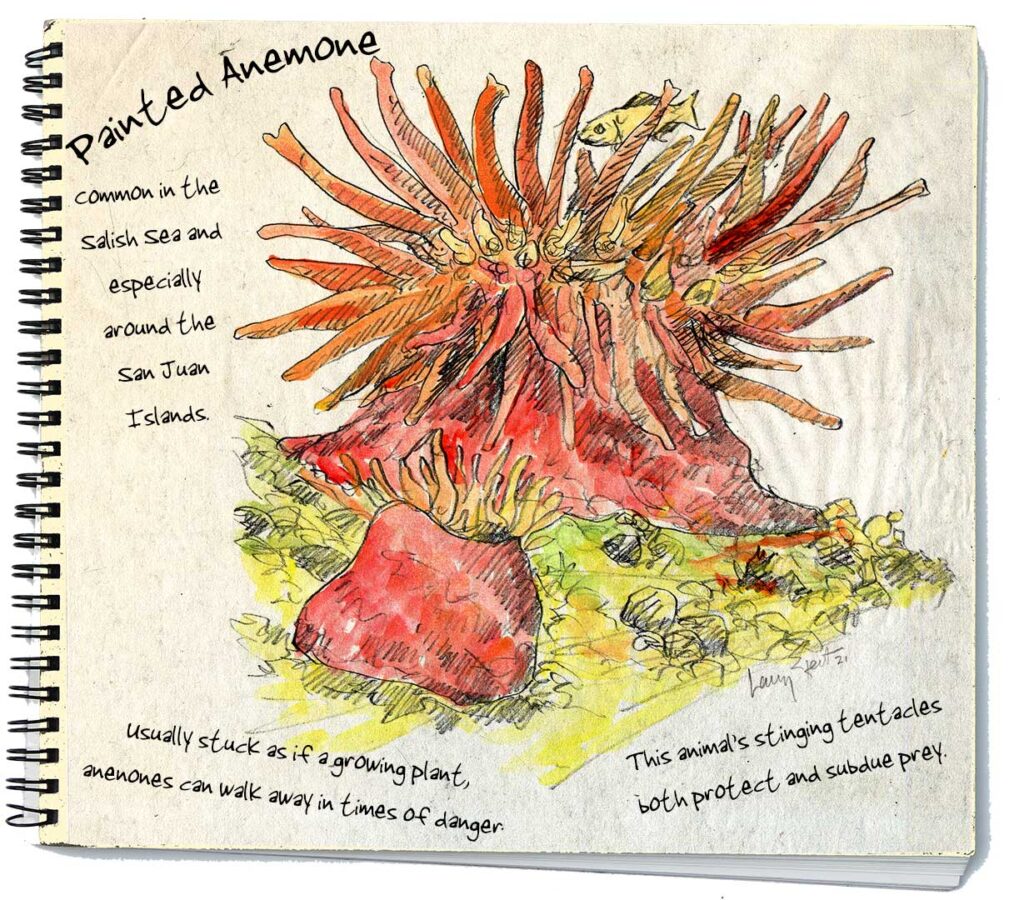

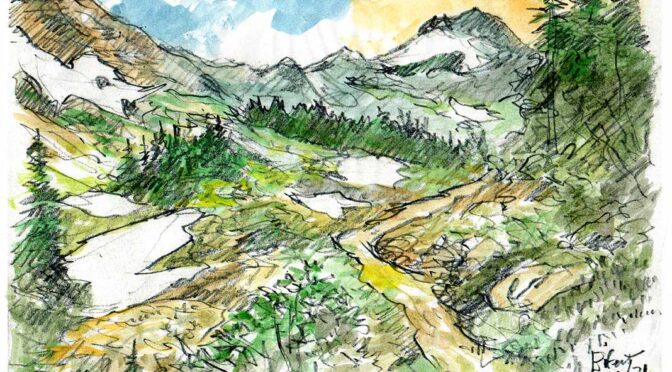

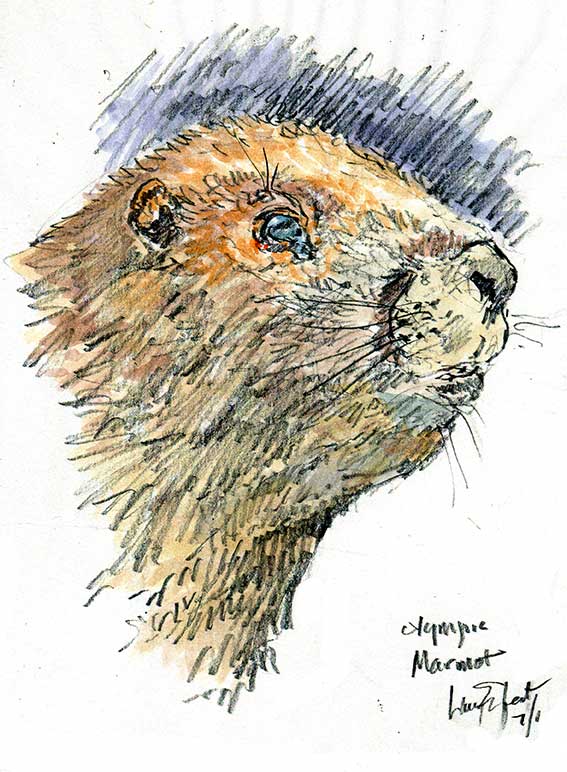

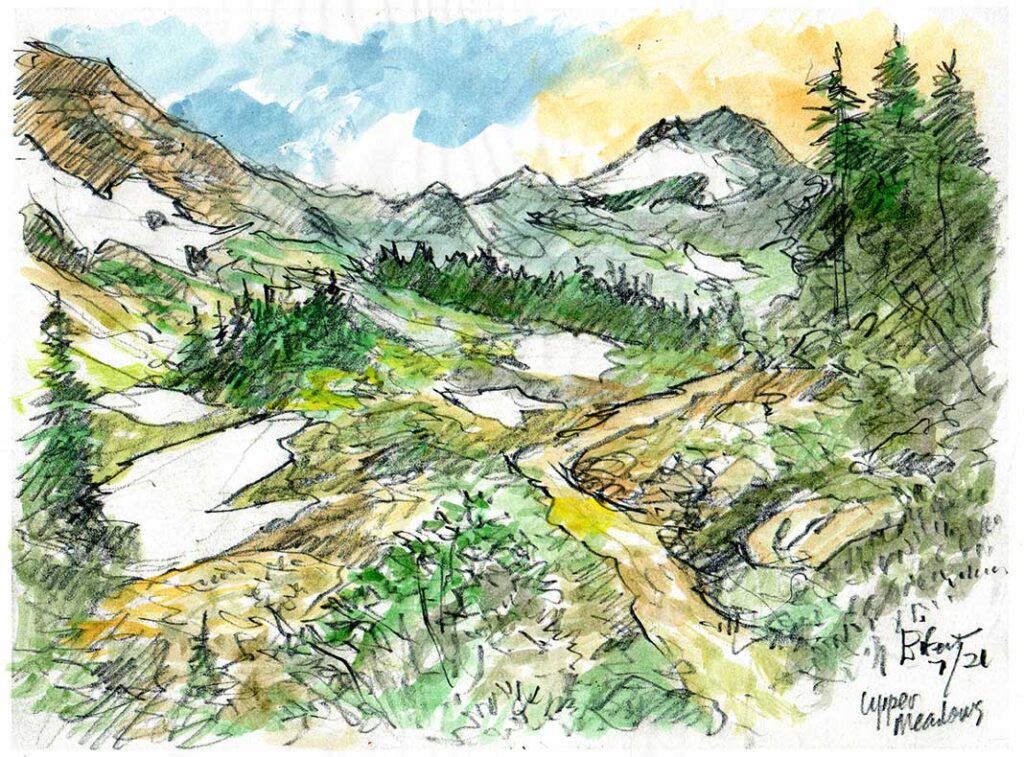

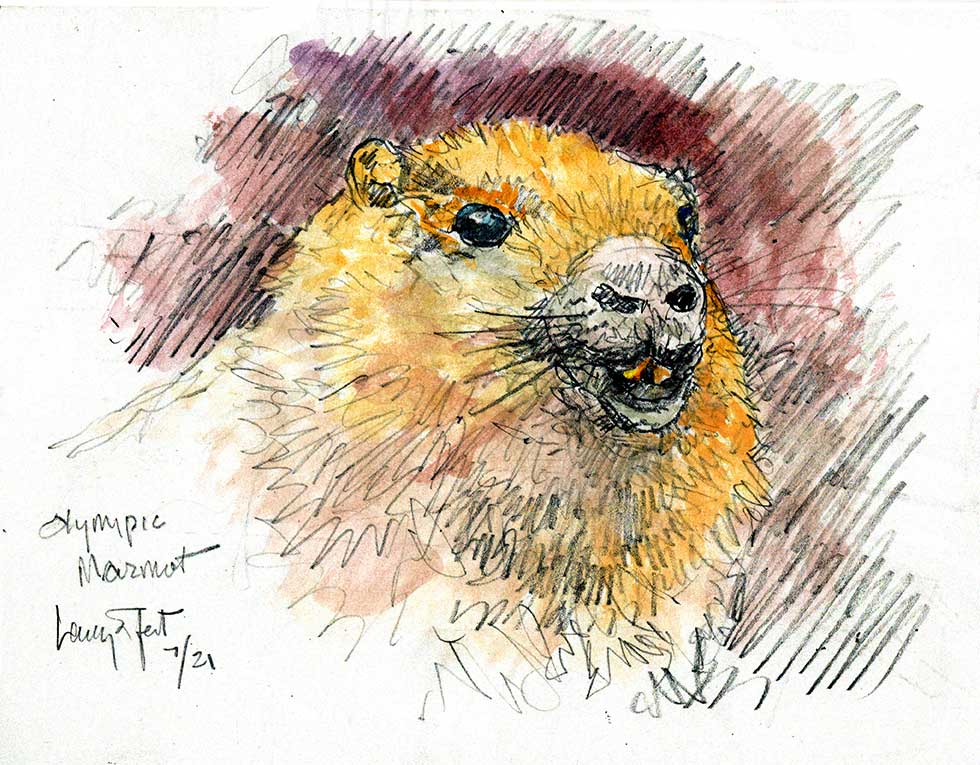

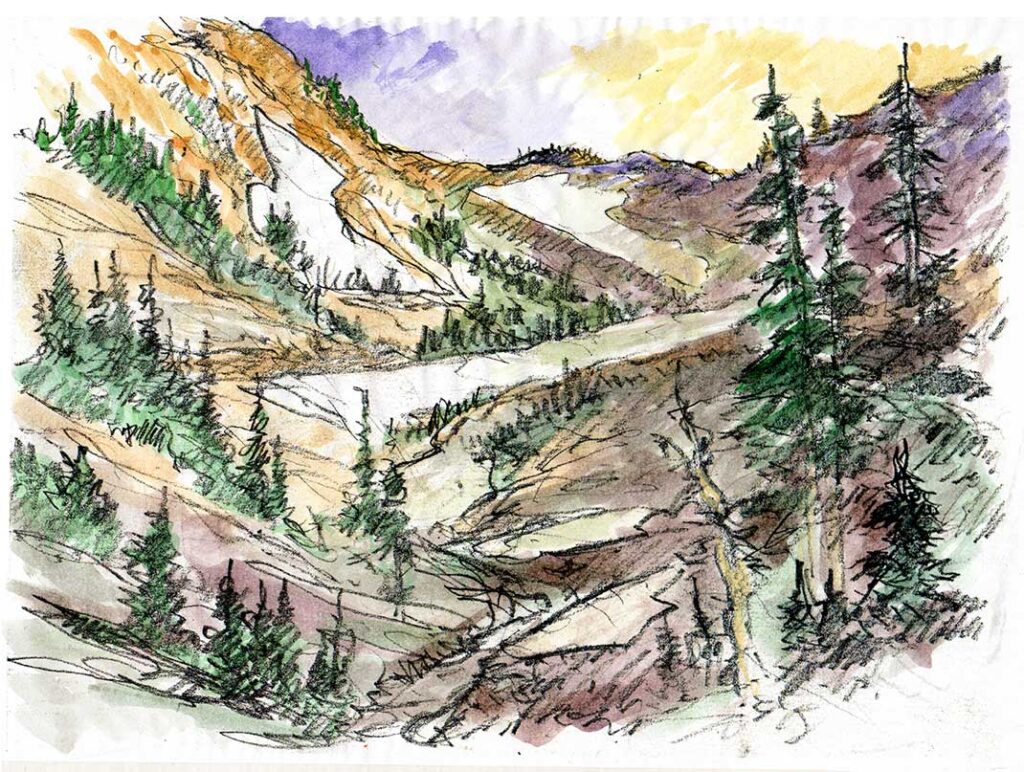

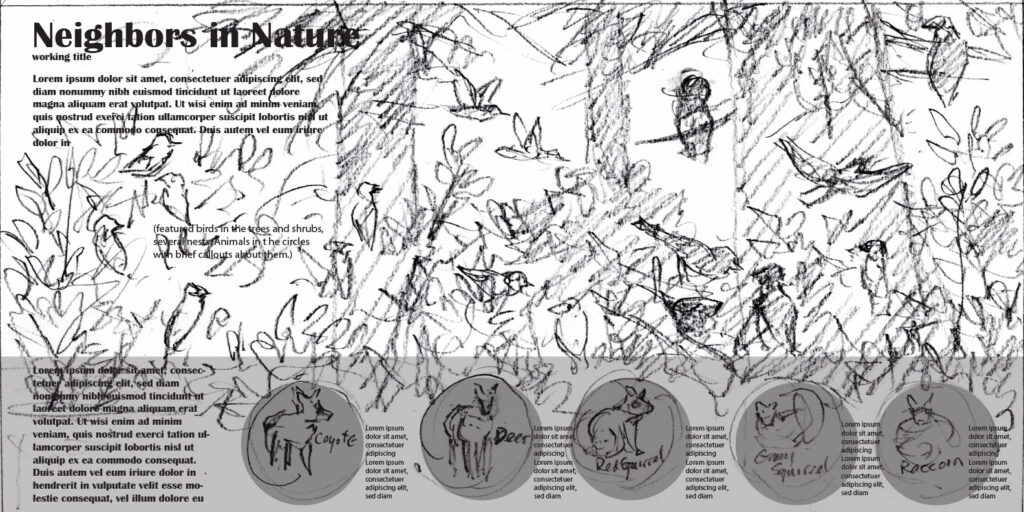

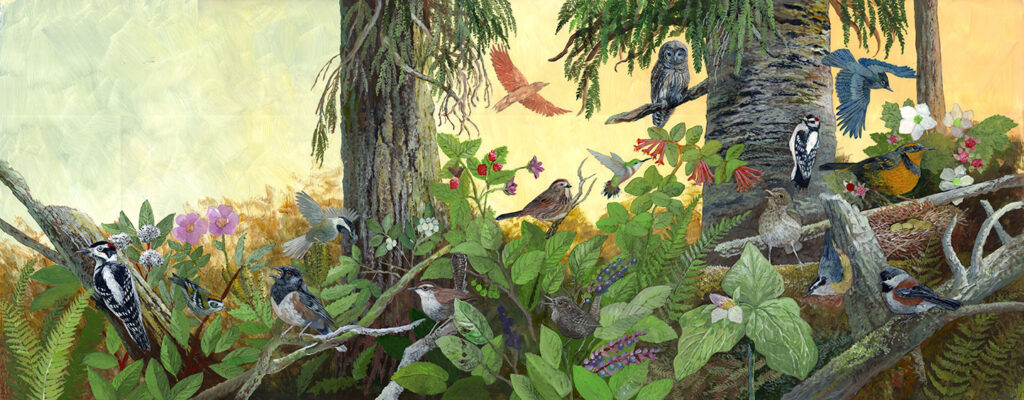

This panel is sort of a nature guide, birds on the top and animals on the bottom. It was a fun image for me to figure out, as these are all the same critters as we have here in our own little forest just 40 miles to the west on the Olympic Peninsula. And I’ll say this, we have better by far, right here in our own meadow. That makes these paintings show how fortunate Nancy and I are to have these acres of trees and critters that feel safe here. We even have old snags that serve as homes for many.

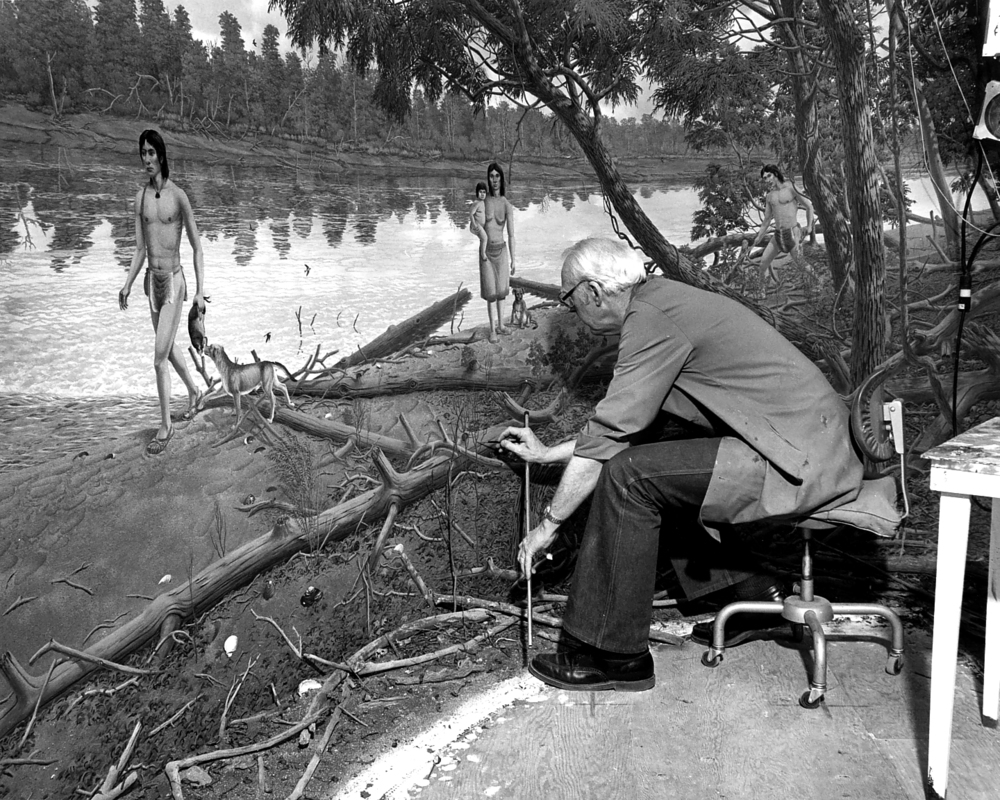

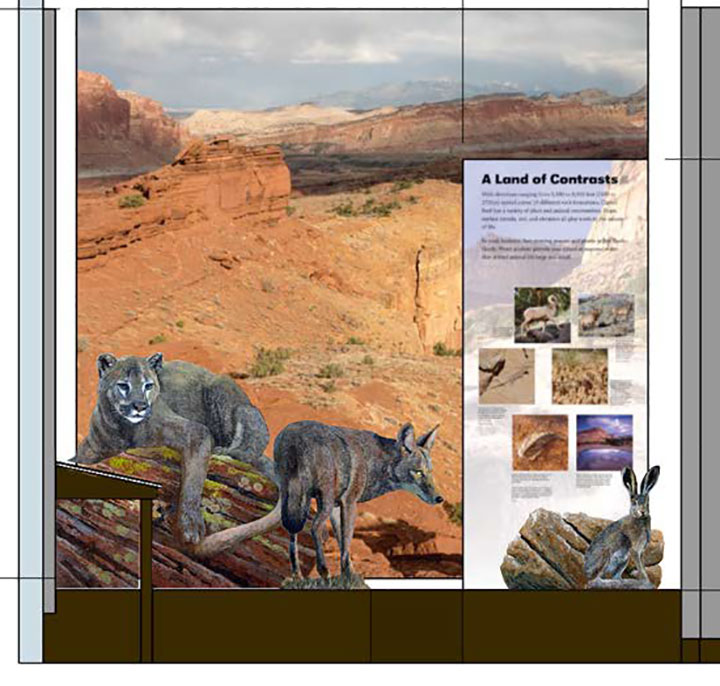

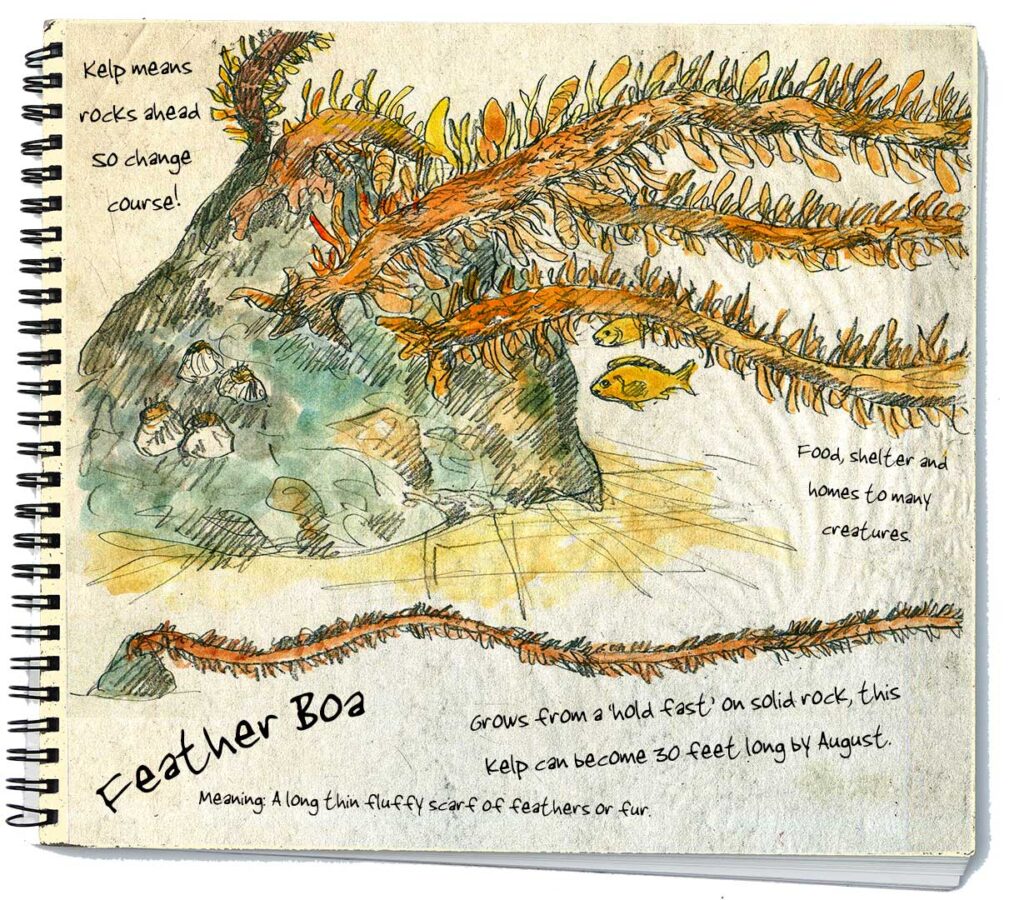

This is the original finished painting before it went into the design. It takes a variety of skills to make these, design, writing, making art and a deep background of the nature. Somehow it all has to come together to make a dramatic and beautiful piece of art that, hopefully, lots of people will stop and learn something. A bit of art in the forest.

And this is the corner of Madison-Morgan Naturescape Park where these two panels are going. The second wayside is being painted now and is coming soon, so stay tuned. Then between 15 and 20 more are going around Silver Lake in Everett, another urban nature park being spruced up by my stuff. In total, I should have about 24 paintings on panels here that will all last beyond my life – it’s a good legacy.

Thanks for reading this week. You can sign up for emails for these posts on my website at larryeifert.com.

Larry Eifert

Here’s my Facebook fan page. I post lots of other stuff there.

Click here to go to our main website – with jigsaw puzzles, prints, interpretive portfolios and lots of other stuff.

Nancy’s web portfolio of stunning photography and paintings.